Transsib – Taiga – Lake Baikal

N 56°0'20.0'' E 92°49'47.0''

Day: 11-13

Russia / Siberia

Location:

Krasnoyarsk

Daily kilometers:

3,036

Total kilometers:

6,562

Latitude N:

56°0’20.0”

Longitude E:

92°49’47.0”

(Photos of the diary entry can be found at the end of the text).

The days on the Transib fly by and are in no way monotonous for us. On the contrary, after all the stress that people have caused us in recent weeks, we enjoy the peace and quiet in our compartment. To be honest, I’m not even prepared to communicate much. We sleep long and a lot, almost like marmots during their hibernation. This is also because the train travels through the time zones without the clocks at the stations being adjusted to the changing time. Moscow time always applies, regardless of whether it is day or night. We only leave our compartment when the train stops a little longer at some stations. Then Tanja takes Ajaci for a walk while I get us something to eat and take some photos. Afterwards we sit in our little kupee, let the taiga fly past us, drink a few Russian beers and enjoy typical local delicacies such as bliny (pancakes), piroshi – baked or fried dumplings with a wide variety of fillings. As my Russian is still rusty, I can’t always find the right words to ask what’s in the dumplings. We are often surprised by curd cheese, mushrooms, cabbage, potatoes, minced meat or chicken. Sometimes I find pelmeni. They taste similar to our Maultaschen. They are mainly eaten as a side dish to a soup, in our case horrible ready-made soups from China, which are bought by many train travelers and are on sale everywhere. There is a lot on offer at the small stalls, unfortunately it often doesn’t taste the same as when the babushka (grandmother or granny) prepares it, but we certainly can’t complain.

Ajaci manages to extend his superstar status even further. In the meantime, we have already received the first offers to buy him. He does his job perfectly and holds out until the various pee stops without complaining. Sometimes we leave the iron queue in the middle of the night. Tanja then takes him for a walk on the tracks or looks for a patch of grass where he can do his business.

Even though we are constantly tired, we leave the train in the cities of Ekaterinburg, Novosibirsk, Irkutsk, Nizhny Novgorod and Omsk. Unfortunately not for long because of the short stays. Memories of our cycle tour through Russia are immediately awakened, as we passed through many towns on our way from Germany to Mongolia that are on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

We stare out of the window for hours, mesmerized. The loudspeaker usually plays Russian music, but at the moment it’s Modern Talking, which doesn’t suit the country at all. The weather is gorgeous and the landscape is everything you read about in the books. Birch forests, spruces, pines, larches and firs, some of which can be up to 800 years old, border the tracks for hours. In contrast to the tropical rainforests, the taiga is characterized by a low species diversity and consists largely of the aforementioned coniferous tree species. I still haven’t really realized the dimensions of this largest contiguous coniferous forest area in the world, which stretches from Scandinavia to Siberia and North America. I can still smell the rich, rustic, clear scent of the forests when we crossed them on our bikes years ago. We often pedaled right past swamps that have developed between the Ural Mountains and the Yenisei. Millions of mosquitoes breed in the shallow waters, which is why we avoided stopping or pitching our tent in such areas at the time. Dead trees stretch their bare, moss-covered trunks into the blue sky. It’s fascinating to think that some of the taiga is still completely undeveloped and that many brown bears roam there. The taiga forest type grows in the temperate and northern latitudes and thus belongs to the non-tropical forests of our planet, which together cover around 14 million square kilometers of land. The extratropical forests mainly thrive in Russia, North America and Europe, but larger areas are also found in Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Argentina, North Africa and the coastal regions of South Africa.

21:30. We reach Krasnoyarsk. “Do you remember how we lived here in the cellar of a monastery?” asks Tanja. “But of course. We were so happy after the bike breakdown when the helpful Sergei picked us up in his truck outside the city and a complete stranger just drove us to the monastery with our bikes,” I say, reminiscing about how Jenya, who picked us up at a petrol station, and his girlfriend Anja became real friends. “It’s a shame we can’t make a longer stop here. They would certainly love a visit,” says Tanja.

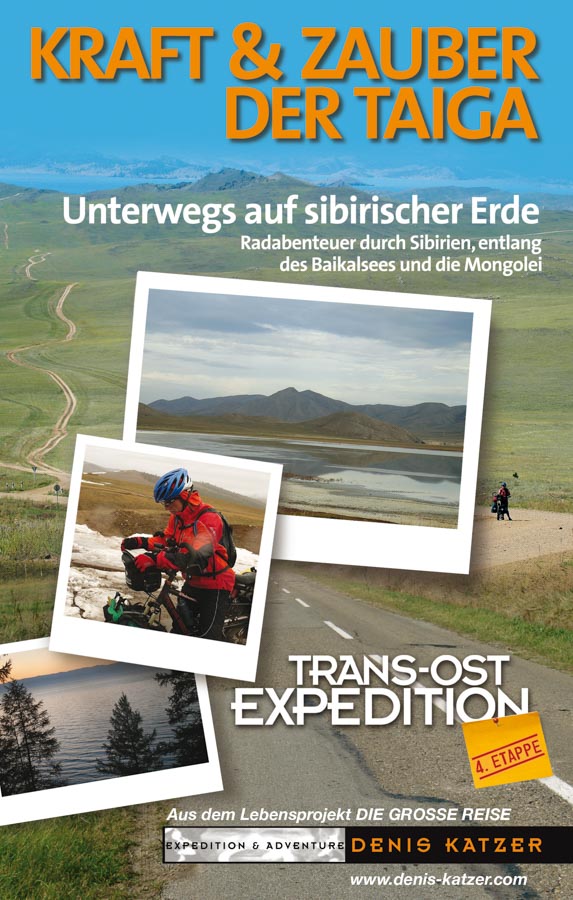

Link to the book click on picture!

After leaving the great rivers Volga, Ob and Yenisei behind us, among others, we reach Lake Baikal in the middle of the night, along which the Trans-Siberian Railway runs for over 200 kilometers. It’s a real shame that we’re passing through what we consider to be the most beautiful section of the entire train journey at night. I sit tensely at the window and try to recognize something. “Look at all the campfires. People sit right next to the deepest freshwater lake in the world and grill their omul (the most species-rich fish in Lake Baikal, which is often sold as a smoked delicacy). I can see the lights of the small tourist town of Listvyanka reflected on the surface of the Father of All Lakes. The Russians adopted the word Baikal, as well as many of the other geographical names for this region, from the tribes living here. The Buryat word for lake was Baigal-nuur. The Mongols called it Baigal-murän or Dalai-noor, which means sacred sea. The Chinese gave it the name Bai-chai, meaning northern sea, to name just a few of the different terms for the lake.

The lake is the largest and, at 25 million years old, oldest freshwater reservoir on earth. One fifth, or 20 percent, of the entire freshwater reserves of our Mother Earth are stored in this enormous trench. “It’s hard to believe. At its deepest point, the bottom is 1,637 meters below the surface. No lake in the world reaches such a depth,” I soon say in awe to Tanja, who has crawled out of her bed and is looking with me at the diminishing reflections of light left by the villages on the surface of the Baikal. Its unimaginably large surface area stretches to 31,492 km², so that even on days with the best visibility you cannot see the other end of the lake. No wonder, since its length from one bank to the other is 673 kilometers. At their widest point, the coasts are 82 kilometers apart. “When you consider that it won’t be long before water is worth more than oil and people start wars over it, Russia, regardless of its enormous natural resources, is the richest country in the world just because of Baikal,” I reflect, as I did in 2009 when we explored the lake on our bikes, and remember that when the Russians discovered this liquid treasure in 1643, they had no idea how valuable the fresh water would one day be for mankind. In total, this oversized basin, which is fed by 336 rivers and countless streams, contains a water volume of 23,000 km³. This makes it larger than the Baltic Sea and corresponds to about 480 times the water content of Lake Constance. With a shoreline length of around 2,125 km, the father of all lakes is the second largest body of water in Asia after the Caspian Sea.

Now that the black, moonless night has sucked all the light out of the landscape, we crawl back onto our bunk beds to get some rest. We are nervous because we don’t want to oversleep our arrival in Ulan Ude tomorrow morning, at 1:00 a.m. Moscow time and 6:00 a.m. Ulan Ude time. “I wonder what damage our bikes have suffered,” I say quietly. “I’m sure it’s not as bad as you think,” Tanja replies sleepily. “I hope,” I say and listen to the incessant ta ta tock, ta, ta tock, ta ta tock of the iron snake.

The live coverage is supported by the companiesGesat GmbH: www.gesat.com and roda computer GmbH www.roda-computer.com The satellite telephone Explorer 300 from Gesat and the rugged notebook Pegasus RP9 from Roda are the pillars of the transmission.