Tunnel rats

N 17°01'12.3'' E 107°06'35.0''

Date:

30.12.2016

Day: 549

Country:

Vietnam

Province:

Quảng Trị

Location:

Vinh Moc

Latitude N:

17°01’12.3”

Longitude E:

107°06’35.0”

Daily kilometers:

15 km

Total kilometers:

21,338 km

Average speed:

24 km/h

Soil condition:

Asphalt

Maximum height:

30 m

Total altitude meters:

58.012 m

Altitude meters for the day:

50 m

Sunrise:

06:19 am

Sunset:

5:27 pm

Temperature day max:

17°C

Total plate tires:

14

Plate front tire:

3

Flat rear tire:

10

Plate trailer tire:

1

(Photos of the diary entry can be found at the end of the text).

“Oh man, I can’t believe it. My shoulder hasn’t even healed yet and at the moment my knee is still a mess,” I moan shortly after waking up. “You’ll be fine. I’m sure of it,” Tanja reassures me. “We made a real rookie mistake. We shouldn’t have ridden 140 kilometers in one day after the long break. Not even with an e-bike. That was just too much,” I continue to lament, because I know that it’s always best to stop on the first few days of cycling when you’re still feeling fit. Of course, the body is not a machine and you should gradually get it used to the strain. If you do not adhere to this unwritten law, it is easy to overstretch or inflame a joint or muscle. The consequences can be nasty. Many a long-distance cyclist has had to break off their journey early because of this fault, or take a week-long break until the overstimulation has subsided.

“I’ll go down to the cellar and get the bikes ready,” I say, as we want to visit the Vinh Moc tunnel system today. “Can you make it there?” “All the way to the cellar?” “No, all the way to Vin Moc?” “That’s only seven kilometers. So if I can’t make it, I might as well dig myself in,” I reply and limp off.

Once in the cellar, I pull the tarpaulin off the bikes and stow them in the dog trailer. My eyes fall on the rear tire of Tanja’s bike. “Not true!” I say, discovering another flat tire. “I’m tearing my hair out,” I curse quietly and start to remove the tire. Check the tire again for foreign objects before you put it back on the rim, an urgent thought prompts me, although I have already looked at the tire twice. Unbelievably, I now discover a shard of glass that has worked its way deep into the tissue and is responsible for the second flat tire in 14 hours. I use the pliers to pull the bastard, which is barely visible from the outside, out of the profile. Then I put in a new inner tube and inflate the tire. After 200 pumping strokes, I feel as if my right upper arm is going to burst, yet no pressure builds up in the tire. I now take the other pump off my bike because I’m afraid that Tanja’s air pump has a fault. After another 50 pumps I’m sweating profusely. Catching my breath, I stop briefly inside and hear a slight hiss. Is the new hose also flat? Annoyed, I pull it out again and can’t believe it when I discover the big hole. It’s like being bewitched. I just pulled in an unpatched old hose. This time I take a brand new inner tube and lo and behold, the tire can be inflated.

It’s 12:00 noon when I come into Tanja’s room, tired from yesterday’s long day, the hours of roughing it on my knees, the total of 500 pumping strokes and the completely unnecessary knee pain, and tell her about my flickodyssey.

At 13:00 we are on our bikes in heavy rain. The stormy wind that blows unchecked across the China Sea makes the palm trees bend and brings tears to our eyes. After just a few kilometers, I realize that it would have been better to give my body complete rest. In addition to the knee problem, the Achilles tendon pain is now flaring up. The intense pain forces me to stop. “I think I’ve dropped a stone in my shoe and it’s pressing on my Achilles tendon!” I shout to Tanja, who comes to a halt behind me. “And?” she asks. “There’s nothing in my shoe, but the tendon isn’t playing ball anymore,” I reply meekly, heaving myself into the saddle to torture myself to the historic village of Vinh Moc.

We’re almost the only visitors to the park in this miserable weather. Before we head into the tunnels, we watch a depressing documentary film about the Vietnam War in the demilitarized zone (EMZ). The zone along the 17th parallel, ten kilometers wide according to the Geneva Indochina Agreement of 1954, separated North and South Vietnam from each other and stretched from the Laotian border to the China Sea. Although the EMZ is an area where no military was allowed to be stationed or moved, and was therefore only open for civilian use, it was in fact one of the most militarized areas in all of Vietnam. In order to disrupt the supply lines to South Vietnam that ran through this sector, the U.S. Army dropped about seven tons of bombs and air mines per inhabitant, devastating this region to an indescribable apocalypse. Despite the deadly continuous hail of bombs, the North Vietnamese in this region did not retreat. On the contrary, after the inhabitants of Vinh Moc village lost their homes, they dug underground with simple tools and their bare hands and built a 2.8 km long underground village in three floors within 13 months between 1965 and 1966, despite constant bombing. They moved 6,000 m3 of earth in the process. According to tradition, 60 families lived down there. Including children, that’s about 300 people.

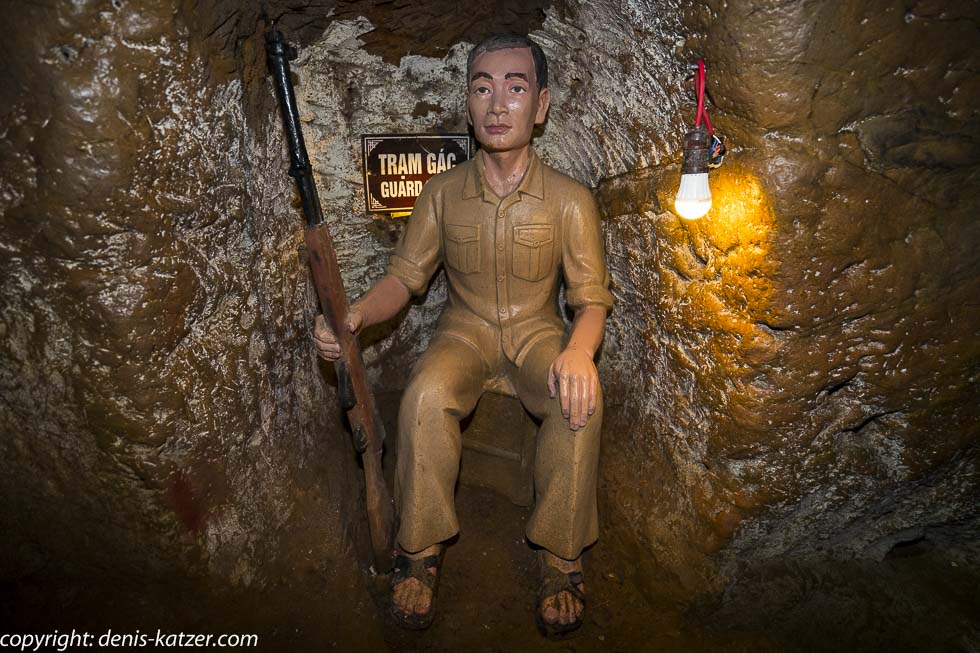

After all the suffering that the movie has seeped into our minds, we feel like crying. The dreary drizzle, the cold and wet weather and my injury cause my condition to plummet even further. Rainy, slippery steps lead down through a narrow opening in the red clay soil. A cold, damp draught can be felt as we descend into the oppressive tunnel system. “At least it’s not raining down here anymore,” I say, holding on to the clammy clay walls to my left and right. Stooping down 12 meters, we reach the first level of the underground site. In tiny living niches (up to four meters deep, 80 cm high and almost two meters wide), which were driven into the limestone rock to the left and right of the passage, we see life-size dolls, which are supposed to convey how people lived here at that time.

We continue downwards. A few light bulbs, which didn’t exist in the past, bathe the corridors in a sad light. In addition, our headlamps help to better illuminate the path into the depths. We carefully slide down the steps to the second floor, which is about 18 meters high. Food and weapons for the resistance were stored here. The inhabitants also used the squat grottoes to discuss actions against the enemy. “Please go first,” say two young men from the Czech Republic, the only visitors we have met so far. The beam of my headlamp falls on a pale face. “Are they not well?” asks Tanja. “I suffer from claustrophobia,” he replies in an uncertain voice. Followed by the two men, we slide down even further. We make our way around a bend into a corridor where the artificial lighting has failed. The two men stop immediately, confer and turn back. During the war, none of the tunnel dwellers were able to turn back, even if they suffered from claustrophobia. They also endured attacks from poisonous snakes, rats and other vermin that had chosen the dark corridors as their home. The enormous heat in summer and the constant humidity during the rainy season were also constant challenges and put a strain on health.

Clear water suddenly flows to the left and right of the narrow path. It’s getting wetter and wetter. The lens of my camera fogs up so much that I have to clean the lens with a handkerchief before every click. Will these corridors be flooded during heavy rain? goes through my mind and I can feel my anxiety growing. If that were the case, they would never have let us down there, another thought reassures me. Just a few meters later, all the water is trapped in a deep well. “That was their drinking water supply,” I say, pointing to the sign above the hole. As we continue on our way, we pass kitchens, storage facilities and even infirmaries and maternity wards. Over the course of two years, 17 babies saw the darkness of the dark world here.

We reach the third and final floor 22 meters below ground. Since American bombs were designed to penetrate 10 meters into the ground, it was relatively safe here. “I doubt that the people here were really protected in the event of a direct hit,” whispers Tanja. “They certainly weren’t. During the bombing, some of the exits of these tunnels were buried. The people who didn’t make it to the last floor in time were buried alive, or simply suffocated further down because no more air could get into the system,” I reply. “But the tunnel system had several entrances, didn’t it?” “That’s right. As far as I know, the builders of Vinh Moc learned from the mistakes of other tunnel systems and dug a total of 13 hidden entrances. If one of the tunnels had been hit by a bomb, the people in this system would have been able to escape via another exit. At least they wouldn’t have suffocated here because there was a good ventilation system.” “In the movie they also said that all the inhabitants of Vinh Moc survived,” says Tanja, plodding through deep puddles. “Yes, they were very careful and didn’t leave their cave system for months.” “Phew, to think we weren’t allowed out of here for months. Unbelievable,” she replied, shaking her head.

A glimmer of light shimmers in the darkness. Curious and careful not to slip, we walk towards him and reach one of the hidden exits on the beach. The China Sea roars, throws its surf onto the yellow sand and hurls the salty spray in our faces. We take a deep breath, glad to have left the oppressive corridors behind us despite the constant rain, and walk along the narrow coastal path, which was under massive fire from warships of the Seventh Fleet with 175-millimeter long-barrel guns at the time.

There’s another entrance,” I say, pointing to a black hole hidden behind dripping wet bamboo. Although we don’t really feel like stumbling through the dark tunnel system again, we go back in. “Since we’re here, we should take a look at everything,” I say. Not far behind the hole in the ground sits an armed Vietnamese guard mannequin. “It was to ward off a tunnel rat.” “Tunnel rats?” asks Tanja. “Yes, I read about that yesterday. It was US, Australian and New Zealand soldiers who went into the tunnel system to fight the Vietcong.” “They had to go down there to fight?” “Yes. Initially, one of the troops was simply ordered down for the mission. He had to take off all his equipment and went into the darkness armed only with a pistol and a hand grenade. Later, they trained soldiers who were better suited to the task than others due to their personal disposition. The Americans naturally recognized the enormous danger posed by the huge tunnel system. It is said that entire areas were tunneled under and that the underground passages were over 200 kilometers long. The Vietcong used this tunnel system to launch surprise, rapid guerrilla attacks against the U.S. military. Even the short-term occupation of the US embassy in Saigon was made possible by the tunnels and is regarded by all historical studies as the turning point of the war. According to an American commander, it was not possible to destroy the tunnel system due to its immense size. Not even by the constant air raids of the B-52 bombers. Even the injection of gas was unsuccessful, as the Vietnamese had installed siphons in their tunnels. In the end, the Americans had to send soldiers down there to stand a chance against the Vietcong.” “An incredible story,” Tanja replies, illuminating the dripping corridor with her headlamp. I follow her carefully so as not to slip. The conversation about the so-called tunnel rats shook me up. My thoughts are literally racing. War is a nightmare for both sides, it goes through my mind and I think about how the US infantry initially didn’t know where the Vietcong came from so suddenly, struck from ambush and disappeared into the void as if by magic. Only later patrols found small, almost perfectly camouflaged holes in the jungle floor. In the beginning, whole troops were sent down there to fight the Vietcong. Often, none of the young soldiers ever saw the light of day again because the narrow tunnel entrances were secured with booby traps, thorns and sharp stakes, for example. Sometimes a spear was thrust between the eyes of the invading soldier by the Vietcong or a trap line when he was about to lower himself into such a hole. In the end, however, the use of the tunnel rats was a sad success because it deprived the Vietcong of the security of being able to hide in its tunnel system…

If you would like to find out more about our adventures, you can find our books under this link.

The live coverage is supported by the companies Gesat GmbH: www.gesat.com and roda computer GmbH http://roda-computer.com/ The satellite telephone Explorer 300 from Gesat and the rugged notebook Pegasus RP9 from Roda are the pillars of the transmission. Pegasus RP9 from Roda are the pillars of the transmission.