4.5 kilometers in the belly of mother earth – Phong Nha Cave

N 17°37'04.8'' E 106°22'35.7''

Date:

08.12.2016

Day: 531

Country:

Vietnam

Province:

Quảng Bình

Location:

Phong Nha Lake House

Latitude N:

17°37’04.8”

Longitude E:

106°22’35.7”

Daily kilometers:

40 km

Total kilometers:

21,042 km

Total altitude meters:

58.432 m

Sunrise:

06:12 am

Sunset:

5:19 pm

Temperature day max:

23°C

(Photos of the diary entry can be found at the end of the text).

With helmet, helmet lamp, life jacket and shoes two sizes too small, I sit in a kayak with Tanja and paddle towards a big yawning black hole. The wide Côn River disappears before our eyes for 7.8 kilometers into the towering rock massif, which belongs to the Annamite mountain range and is part of the largest limestone area in the world. Just a hundred meters to go before we paddle into one of the most beautiful and longest river caves in the world, originally discovered by a Frenchman but only explored by British speleologists in 1990. “You will be one of the few people on earth to be able to admire a strange world with the most beautiful underground sandbanks and reefs, the widest caves and the most sensational stalactites and stalagmites,” enthused Alex, the receptionist at Lake House, to us this morning.

We watch excitedly as the six red and yellow kayaks in our group disappear into the mouth of one of the largest caves in the region. As soon as the gorge has swallowed us up, it gets dark. However, our eyes quickly get used to the diffuse light inside the mountain. The first few hundred meters are lit up by electric spotlights that illuminate the enormous and breathtakingly beautiful stalactites and stalagmites. “Awesome,” I hear Tanja say, her paddle splashing into the water to the left and right of her. “Now I know why Phong Nha is called the Cave of Wind Teeth,” I say, feeling the damp breeze at my back. Despite the poor light, I try to photograph the enormous stalactites, which are around a hundred million years old and, with a little imagination, do indeed look like oversized dragon’s teeth. “Shit!” I curse loudly as water drips onto the camera from the cave ceiling. “Bad?” asks Tanja. “I hope not,” I reply and dry her off with a towel that we took with us as a precaution. I quickly pack the expensive electronics back into the waterproof rucksack. “We have to hurry,” Tanja warns us, as our group has disappeared around the next bend in the river.

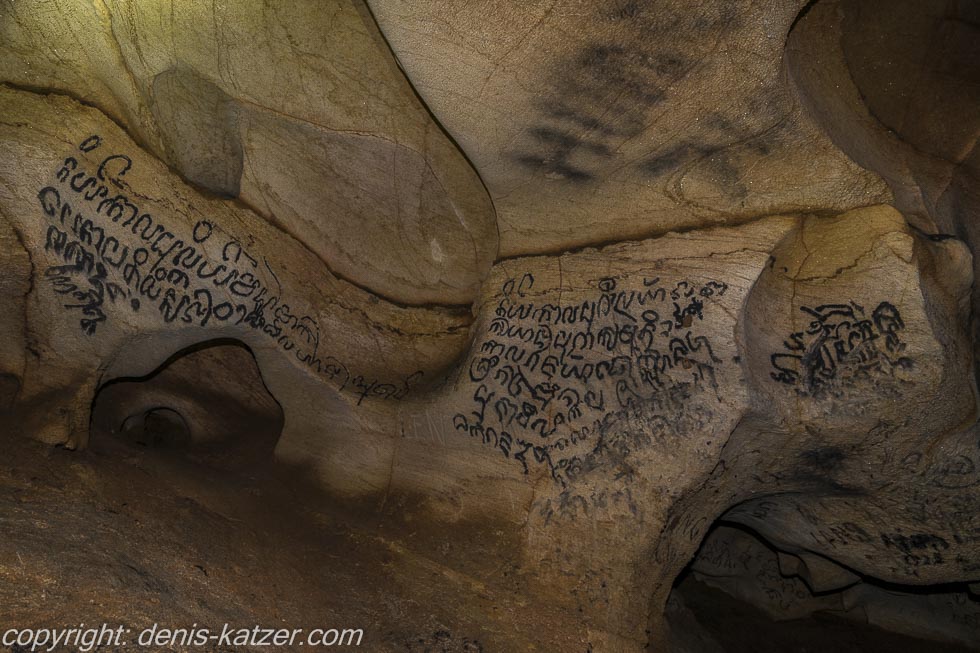

Luong, our guide, points to a sandy beach where we are to dock. Accompanied by Bao and Anantakarn, the two porters carrying food, spare batteries and first aid kits, 11 excursion participants from Brazil and Australia leave the kayaks with us, trudge up the sandy hill and walk through an oversized rock tube. None of those present speaks much. The sight of the river cave is as if we have entered an alien planet. Luong points to a rock blackened by soot and tells us that during the Vietnam War there was a hidden emergency hospital here where the wounded were operated on and cared for. I listen into the darkness and hear drops splashing onto the wet ground from the 30-metre-high cave ceiling. While Luong tells me about that time, I move away from the group to take a few photos. As I do so, I hear the incessant sound of water droplets echoing off the walls even more than before. Was someone whispering? Was that a moan? I shake my head. Some of the stalactites resemble ancient creatures. Suddenly feeling a little uneasy, I hurry back to the group across the slippery ground. “And here, on these rocks, you can see the writing of the Cham people. They ruled central Vietnam in the first millennium. During their heyday between the 6th and 10th centuries, they controlled the entire spice trade in Southeast Asia.” As Luong continues, I shine my headlamp over the black text. “Even back then, the Cham had extensive trade relations with Japan, Arabia, India and China and also possessed a considerable naval fleet. They later converted from Hinduism to Islam.” I wonder how they got so far into the cave at that time? The Cham didn’t have high-tech lamps like we do. And why did they paint the characters on the rocks, I wonder?

20 minutes later we continue our excursion in the kayaks. The last artificial lighting is long behind us. Only small guided excursions like ours can reach this dark, wet underwater world. In the light of our headlamps, we follow the song as it winds its way through the mountain. Then the river suddenly disappears under huge stalactites that have broken off from the ceiling. We leave the boats and continue the cave tour on foot. The participants climb over massive, sometimes dangerously slippery rocks. Some yawning gaps are bridged with a rusty, narrow metal ladder. We carefully balance over it. Hands shimmy down a steep slope on strong ropes. From time to time we hear the rushing of the river below us and almost everywhere the beam of our headlamp falls, the most beautiful stalactites grow from the ceiling and mighty stalagmites strive upwards. Never in my life have I seen such subterranean splendor. Not in my wildest dreams could I have imagined these wonders of the earth. Under the spell of the river cave, we stalk over razor-sharp rock. Because I’m holding the camera in my left hand to document this fascinating world, I can only secure myself to the rock faces with my right. I follow the person in front of me particularly carefully and watch where he puts his foot. The strong hands of Luong, Bao and Anantakarn help at particularly critical points. Just one misstep and you would seriously injure yourself here. None of the participants have any climbing experience and the fitness level of one or the other is certainly not what is urgently needed on such a tour. “Luong?” I ask our guide as I pull myself up on a rope close behind him. “Yes?” “Hasn’t anyone ever broken anything on this tour?” “This part of the cave hasn’t been accessible for too long. So we don’t have much experience yet, but so far there have only been minor injuries,” he replies, looking friendly. Whatever minor injuries are? I think, highly concentrated, putting one foot in front of the other, and I am sure that Luong has been told to answer like this so as not to damage the business with the caves.

Because my special non-slip shoes, which I got from the organizers, are two sizes too small, I can now only walk with pain. “That’ll certainly give you blue toenails,” I say to Tanja, who is climbing up a rock close behind me. “Maybe you should have gone with your tracking shoes after all.” “Luong said that wouldn’t be a good idea because of the slippery surface in the cave and that other participants before me had survived the tour with size 45 shoes.” “Luong. Why doesn’t your company have bigger shoes?” I ask him as we trudge through knee-high, cold water. “We are much smaller than you. It’s difficult to get shoe sizes like that in Vietnam. I hope you can hold out a little longer. We’ll stop for a rest in an hour at the latest, then you can take those little things off for a while,” he says with a laugh.

“Everyone, please listen up! Everyone carrying a rucksack leave it here now,” says Luong, standing in a large grotto, the sandy floor of which is as flat as if someone had drawn it with a ruler. It gurgles and gurgles incredibly loudly in front of us. The mass of water emerging from the black rock shimmers in the beam of the headlamps. The song flows deceptively lazily past us and disappears into the darkness outside the range of our lamps. A finger-thick rope, about 20 meters long, is stretched from our shore to the other. “Because it has rained a lot in the last few weeks, I don’t know how strong the current is. I’ll swim ahead and let you know if we can make it to the other shore or if it’s better to leave it alone today,” says Luong. “They’re seriously going to let us swim over it?” wonders Tanja. “I hope,” I reply, as this trip is exactly to my taste. “All right. I think it’s okay,” Luong calls over from the other side. His words echo off the walls and drown out the loud roar of the river. One of the Brazilians carefully climbs over the razor-sharp rocks into the underground stream. “Hold on here,” says Anantakarn, who is up to his hips in water and gives instructions so that none of the participants are swept away by the floods. “Ready,” Anantakarn asks. “Ready,” replies the Brazilian and jumps onto the rope. “Don’t let go!” Anantakarn calls after him as the well-trained young man pulls himself across the river. The current takes his body with it so that he hangs from the rope at right angles. Suddenly, the Brazilian opens his eyes and turns his head frantically in all directions. “My GoPro camera!” he shouts, startled, and is about to let go of the rope to swim after it. “Hold on!” shouts Luong. Don’t let go of the rope under any circumstances, I think, watching the scene spellbound, remembering how as a 16-year-old boy I tried to rescue a kayak that had been kicked loose while white water rafting. Suddenly, the current swept me along and drove me under a tree lying above the river. Only the courageous and quick help of my experienced companions saved my life. Fortunately, the Brazilian reacts wisely and continues to pull himself along the rope until he reaches the other bank safely. Meanwhile, Luong searches the river surface with a powerful flashlight. “It’s gone,” he says. “Does the river disappear back there under the rocks in the dark?” I ask him. “Yes.” “It’s a good thing the Brazilian didn’t swim after his camera. That would have pulled him in with the current.” “Yes, good,” Luong replies soberly. Then it’s Tanja’s turn to shimmy across the river. “Don’t let go. Do you hear me?” I say. “Sure,” she replies, plunges bravely into the cold, black water and pulls herself hand over hand to the other bank. I am amazed, none of the participants chickened out before the river crossing. Because we would have to come back the same way later, that would have been a real alternative. On the other side, we continue our way through the cave. We walk over sand hills at least 15 meters high, through narrow passages and cliffs, until we reach a point where we can go no further in today’s high water level of the Song. “At this point we are about 4.5 kilometers inside Phong Nha Cave. From now on it gets even narrower and more dangerous. We’d better turn back,” says Luong. On the way back, we climb the underground sand dune again. “Everyone sit down in the sand, switch off your headlamps and keep quiet for a few minutes,” Luong tells us. After the last person has switched off their headlamp, we are enveloped in all-encompassing blackness. There is nothing left to see, not even the slightest light. Absolute darkness surrounds us in a hostile environment. If any of us had claustrophobia, we’d be panicking by now at the latest. I listen into the boundless darkness, hear the roaring, gurgling and gurgling of the song and the thudding of the many drops of water on the rock. An orchestra of the underworld that stretches over 126 kilometers with at least 300 other caves and grottos, and researchers discover new caves in this region every year. It’s fascinating what our Mother Earth has to offer and it’s a good thing that UNESCO declared this cave a World Heritage Site in 2003.

On the way back, the river crossing runs smoothly. Luong leads us through enchanting sinter pools which, were the water not so cold, would tempt us to take a dip. Then, to the displeasure of the Brazilians, we go through tributaries of the Song River so that we don’t have to do sections twice. We wade through waist-high cold water from which stalactites protrude like spearheads. Because of the darkness, the reason is not recognizable. A woman behind me slips and hits her knee on one of the sharp-edged rocks. Leaning on her husband’s shoulders, she hobbles on, her face contorted with pain. Back in the cave, where we have left our rucksacks and I have fortunately left my camera, our companions spread out a tarpaulin on the sandy, flat ground and serve us a late lunch. “How are your toes?” asks Tanja. “They will certainly turn black and hopefully not fall off,” I reply. On the way out of the cave, I find it harder and harder to walk and when we reach the kayaks, it takes a load off my mind. My toes actually turned black the next day and yet I wouldn’t want to miss this unique, unforgettable, enriching experience and would do it again any time. But with matching shoes…

If you would like to find out more about our adventures, you can find our books under this link.

The live coverage is supported by the companies Gesat GmbH: www.gesat.com and roda computer GmbH http://roda-computer.com/ The satellite telephone Explorer 300 from Gesat and the rugged notebook Pegasus RP9 from Roda are the pillars of the transmission. Pegasus RP9 from Roda are the pillars of the transmission.