One of the most dangerous photo hotspots in the world, 1000 meters above the abyss

N 59°54.00.5'' E 006°46'42.5''

Date:

27.08.2020

Day: 025

Country:

Norway

Location:

Kjeragbolten

Daily kilometers:

54 km

Total kilometers:

2665 km

Soil condition:

Asphalt

Bridge crossings:

3

Tunnel passages:

0

Sunrise:

06:17 h

Sunset:

8:57 pm

Temperature day max:

17°

Night temperature min:

11°

Departure:

09:00 a.m.

Arrival time:

21:00

(Photos of the diary entry can be found at the end of the text).

Click here for the podcast!

Link to the current itinerary

(For further contributions click on one of the flags in the map)

“Tanja, hurry up, they’re closing the road.” “What, the road?” “Yes, they obviously want to repair the road surface. I hope they’ll still let us through.” We hastily jump into our clothes, put the dishes in the sink, stow the two pots in the cupboard, order Ajaci into his co-pilot’s seat, check that all the windows and doors are locked and leave the plateau. “Can I get past there?” I ask Tanja, because the construction vehicle that has blocked off the road barely leaves any room. “It’ll be close, but you’ll manage.” A few moments later we are behind the blockade and ride the last 7 kilometers to today’s destination. The narrow pass road winds a few hundred meters into the valley. I shift down to second gear. The engine roars and slows the Terra down. Although we are driving with this gear reduction, I also have to keep stepping on the brakes. The 6.2 tons push and press us down the steep mountain road. We reach the large private parking lot where everyone who wants to go on the Kjeragbolten hike has to pay €30. “Shhh,” says a tanned man at the entrance to the parking lot, holding his index finger in front of his mouth. It is the boss of the plant. “I heard you from a long way off,” he laughs. “Yes, the engine brake is quite loud,” I reply. “And you want to go up there?” “Yes, absolutely.” “You’ve chosen good weather. It rained every day in July. But August is much better. When angels travel. Ha, ha, ha. Please park your beautiful expedition vehicle in the square there and buy a ticket. Once you’ve done that, please come and see me again. Then I’ll show you the best spot on the map from where you have a great view of the fjord. The official viewpoint is not so good. So it makes sense to leave the route for a few meters.” “Oh, that’s very nice. You Norwegians really are a friendly people,” says Tanja. “Ha, ha, ha, I haven’t met any like that yet. Most of us are very introverted and don’t want to have much to do with others.” “Then you’re obviously different.” I also note with a laugh. “I live in Florida during the Norwegian winter and in the summer I’m here managing the place.” “Sounds like a good way of life”. “Not as good as yours. Would also like to travel around the world. From what I read on your mobile, you set off to travel the world back in 1991. Is that true?” “Yes, we’ve been doing nothing but exploring Mother Earth and her inhabitants for ourselves since 1991.” “Ha, ha, ha, I haven’t met anyone like you yet either. That’s really great.” “What’s your name anyway?” I ask. “Oh, my name is Henrik. And you’re Denis and your pretty passenger is called Tanja.” “You seem to be psychic?” “I can read well, ha, ha, ha. It’s written big and wide on your vehicle.” “Do you think you can take a dog on the hike? According to the description, it’s not supposed to be easy.” “You can definitely take your dog with you. He’ll have an easier time with his four feet than you will.” “Are you sure about that?” “Absolutely. He’s the right size and if he’s an adventurer’s dog, he’s certainly in good shape.” “Yes, that should be enough,” says Tanja confidently.

We quickly shoulder the rucksacks we have prepared for today. I strap on my new camera belt, click the camera in, lock the Terra and off I go. As soon as we leave the parking lot behind us, the road climbs steeply. To secure the hikers, iron chains are installed on which you can shimmy upwards. After just a few hundred meters, I get a nagging pain in my lower back. It feels like someone is squeezing the air out of me, only it’s not the air but the energy. Tanja and Ajaci quickly lose me. I can’t believe it. “Am I really that unfit?” With every meter I walk, I find it harder to put one foot in front of the other. A few young hikers climb past me. They are also panting hard, but compared to me they don’t seem to have the slightest difficulty. “Are you OK?” I hear Tanja’s question. “I’ll be fine,” I vow, not admitting to myself that if the pain doesn’t stop, I’ll have to give up at the start of the tour. “The adventurer has to give up on a hike. That’s not possible. I walked 12,000 kilometers with camels through life-threatening deserts, crossed Australia on foot with Tanja, rode and walked through Pakistan and Mongolia, and now I’ve given up after just a few meters of altitude. No, no, no.” I work my way up with great difficulty, hanging along the chain. The parking lot directly below me is only slowly getting smaller. “How long should it go up like this? 2 ½ to 3 hours, they said. No chance, I won’t make it. I don’t just have to get up, I also have to get back down. Many mountaineers make it to the summit, but the challenge is not just climbing a mountain, but descending safely and arriving safely in the valley.”it goes through my head. “We can take a break,” Tanja suggests sympathetically when she recognizes the look on my face. “After 33 years, I can’t fool her. She knows I’m at the limit.” “Yes, maybe we should stop for a moment,” I admit to myself, even though we’ve only been on the road for 15 minutes. “What’s the matter? Is there something wrong with you?” “I have pain in my back and I don’t know where it’s coming from. I find it difficult to take one step in front of the other. Somehow both hips are locked,” I say. “Should we turn back?” “I don’t know. I’ll try another few hundred meters.” Five minutes later, I click the camera off my camera belt to take a picture. I even find it difficult to take photos. Suddenly a strange thought crosses my mind. “Is it the camera belt? Could it be that it’s pressing on a nerve?” Even though I don’t really believe it, I stop and take the rucksack off my shoulder. Then I unclip the camera belt from my hip, stow it and the camera in it and carry on walking. It is difficult to take pictures this way, but it is worth the effort. If things go on like this, I won’t be able to take any more pictures of this mountain climb anyway. “I can’t believe it. It’s as if an invisible hand had removed my shackles. The pain is instantly gone. Even my hips are free again,” I cheer inwardly. “Tanja! It was the belt! It must have pressed on a nerve. It’s hard to believe, but everything is back to normal now and the pain has disappeared,” I say with relief when I catch up with her. “I can well imagine. If acupuncture and acupressure work, then it’s also possible that a belt like this can have an effect on the body,” she muses.

From this point on, I enjoy the excursion and the impressive view from up here. It’s the same spectacular lunar landscape that we drove through on the Terra yesterday, only this time we’re hiking through it. Our Ajaci completely amazes me. He climbs and jumps up the steep rocks as if he were a mountain goat. “You’ve got a great dog there,” praises an Englishman. “It’s not a dog. He’s originally a cross between a polar bear and a wolf, but now I think he’s a cross between a climbing monkey and a mountain goat,” Tanja replies proudly and with a laugh. “Ha, ha, ha, monkey and mountain goat are good qualities for such a steep tour,” he says.

Once we have reached a ridge, we descend again via steps, some of which have been created by human hands. We cross a few streams with crystal-clear water and pass through a swampy, wet valley. Climb back up over steps, some secured with iron chains. I feel great, freed from my belt, which until recently made running almost impossible. We climb over rock with a good grip, over smooth rock polished by the last ice age and glaciers. “How far is it to the top?” I ask two young Indians. “Do you see the rise there?” “Yes.” “You have to go up there, then over a high plateau. From there, it’s not so steep until you reach Kjerag,” they explain. The sight of the steep ascent is a little intimidating. We take a few photos at a mountain hut, just like in the German Alps, then we continue on and work our way up the slope. The weather is perfect for such a sometimes dangerous hike. Not to think how slippery it must be here when it rains. Let alone in winter, when you can only get up there with special equipment and an expert mountain guide.

We reach the plateau. Smaller patches of water lie in ancient glacial basins, a few grasses grow on the banks, sometimes scattered, hard-boiled flowers stretch their blossoms into the blue sky. A fierce gust of wind blows out of nowhere, bending the delicate grasses and flowers and fizzling out into the vastness of the stark mountain landscape. Ajaci drinks the meltwater, loves it, can’t get enough of it. “It’s amazing how much water a dog can drink,” I think to myself. Snow and ice fields lie to our left and right in deep crevasses and gorges. Permanent shade has allowed them to survive the summer. We reach a narrow gorge. Climb inside. At the end of this passage, the famous five cubic meter boulder is said to be wedged between two rock faces, on which one or the other brave person can be photographed. I’m curious to see if it’s really as spectacular as some Instagram posts make it out to be. And suddenly, after two and a half hours of scrambling through the Norwegian mountains, we find ourselves in front of it, one of the most dangerous photo hotspots in the world. A couple of hikers stand there with their cameras at the ready, taking photos of a young man posing on the boulder wedged between two sloping rock faces. “Wow,” I exclaim, because the sight is beyond my imagination. “Come on, get on it,” two Frenchmen urge their friend to climb the boulder. From the photographers’ position, we catch a glimpse of its head peeking around the edge of the cliff. His face can be seen briefly, then disappears again. “I’ll go up and have a look,” I decide, while Tanja stays here with our camera to get a photo of me in the box. “What is it?” I ask the young Frenchman, who is trembling all over as if he has just seen the devil himself. “I’m afraid of heights and don’t dare climb the rock. “Then you’d better stay there. There’s no point risking your life just for a photo,” I reassure him, only now realizing what he’s talking about. Unbelievable. To climb to the most famous and one of the most dangerous photo hotspots in the world, you have to cross a rocky ledge that slopes down to nowhere. It is an estimated two meters long, bordered on its right side by the rock massif and offers those who dare a tread of 30 or 40 cm. If you stumble or sway on the narrow footbridge, you fall 1084 meters before hitting the rocky shore of the fjord. “Crazy, just crazy,” is what goes through my head. No wonder the Frenchman is trembling. Anyone who climbs over there must be insane, absolutely tired of life or deathly courageous. “Don’t think and don’t look down under any circumstances,” I say to myself as I take the first step onto the narrow path of the ledge. An unbearable, almost indescribable feeling immediately runs through my body. Each of my cells screams. “Don’t look down,” I warn myself. The Frenchman is now behind me and watches me silently. Second step, third step, then the gap is in front of me, on the other side of which the skirt is tucked in. So one gap on my side and one on the opposite side. In between is the five cubic meter boulder that now needs to be stepped on. Although the gap is only narrow, I can see the depth flashing up in the corner of my eye. “What madness.” I get down on my knees, unable to stand upright on the skirt on which many a brave or crazy person has their picture taken for an Instagram photo. Like an animal, I am now chewing on the famous rock on all fours. Fully aware that I’m now descending 1084 meters in all directions in just a few centimeters, my muscles almost fail me and what’s worse, they start to tremble uncontrollably. “If normal, untrained people can be photographed here, why is it so hard for me to keep my mind under control and why do I feel like my body is going to spiral out of control at any moment?” “Go to the side! You’re ruining the picture!” shouts the Englishman, who complimented Ajaci as he climbed. “You have to step a few meters to the side!” he shouts again, because someone is standing next to the skirt on the plateau. “Thank you!” I hear Tanja shout as she takes the photo for which I am undoubtedly putting myself in danger. As a former instructor in an elite unit, as a parachutist, paraglider pilot and after all the sometimes highly dangerous adventures and expeditions we have gone on in our exciting lives, I am surprised that this thing is bothering me. “Has the Frenchman infected me with his fear? Do you take on the other person’s energy?” my thoughts swirl. “Crazy, just crazy,” continues to run through my head as I slowly rise from my crawling position. My knees are shaking. Nobody notices, but I can feel it. Then I stand. A single gust of wind would blow me down here. Luckily the weather is good. “Take the photo!” I yell. Tanja stands down there, apparently calm as a cucumber, and tries to ask another one of the idiots in the picture to take a few steps back. “I don’t care! Take the photo!” I shout, thinking of nothing else but leaving this fucking rock immediately. Then I raise my arms and think I’ve achieved a great feat, although I’m aware that one or two fearless people will even jump up for a good photo on this rock. Tanja shows me the Thumbs Up sign. With great concentration, I turn my body 90 degrees, lift my foot, step over the gap onto the narrow ledge of the rock slab, step one, two, three and then I’m back on safe ground. “Absolutely crazy,” I say over and over again. “Is there anything wrong?” I ask Tanja again. “I don’t know yet,” she replies, looking at the pictures in the camera. “I hope so, because nothing is going to get me up there any time soon. I’m still all shaken up. It’s an amazing experience and I don’t think you should climb the rock. It’s definitely too dangerous,” I say and tell them what I felt and experienced up there.

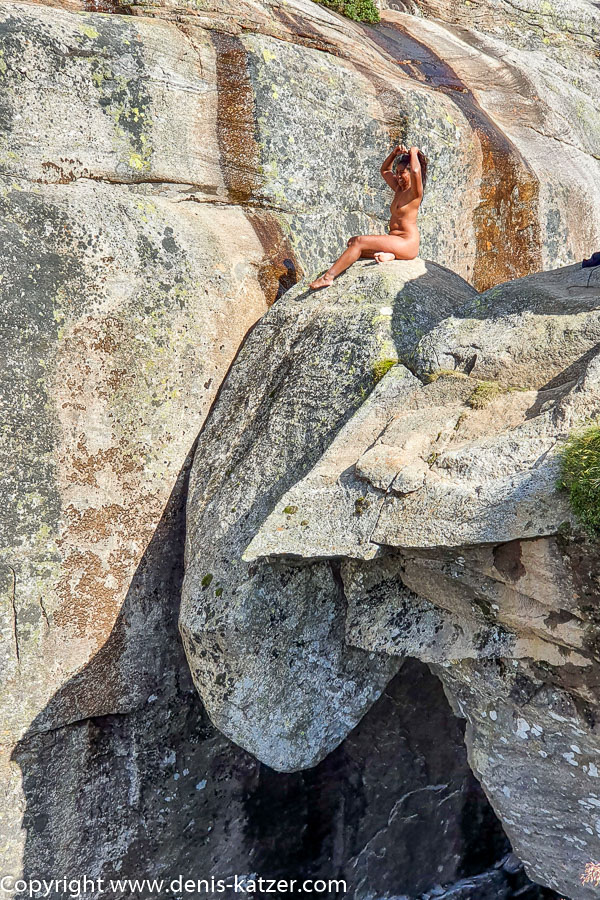

We sit down on the plateau next to the rock and have a snack. Ajaci also gets his well-deserved meal. “I don’t understand why the Norwegian government is allowing this,” I begin to give free rein to my thoughts. “What do you mean?” “Well, a lot of things are forbidden in this country and everything is somehow regulated. And on the other hand, anyone who wants to is allowed to climb this monolith. Just to be able to show something special on their Instagram account, they risk their heads and necks. That’s pure madness. Yes, I know, I was on there too. Maybe motivated by all the photo hype. Somehow I find the situation decadent and almost a little repulsive. You have to be careful not to get infected by all this nonsense. Due to our extreme overconsumption and because we throw everything away and can no longer have it repaired, our planet is being destroyed at this very moment. On the other hand, there are the newly awakened nature lovers who advertise the last beautiful spots on earth on their accounts to give themselves an advantage. And then we stand up here, take a crazy photo like this, only to end up infecting even more people to do the same. It’s a crazy world we’re all trapped in together. It feels so hopeless. It’s almost a little desperate,” I say, looking down at the Lysefjord 1084 meters below us. “I think the experience you’ve just had on the monolith has stimulated your thoughts. You are undoubtedly right in what you say, but don’t spoil your mood in this unique place,” Tanja replies. “Hm, sure, this might not be the right place on earth to discuss the world and its crazy inhabitants, but… maybe the here and now is the right moment. According to my research, around 259 people died from selfies between 2011 and November 2017. In the same period, around 50 people died from shark attacks. Imagine that. They died because they stood on a monolith like this one,” I say, still a little excited, pointing at the boulder wedged between the rock faces just 10 meters away from us. “I can’t believe it. Look at that!” exclaims Tanja. I jump up in dismay and look at the ball of rock on which a young Indian woman is sitting at this very moment. That wouldn’t be so unusual, except that she poses stark naked in front of her girlfriend’s camera. “How far will man take it? Where is the end? Sex sells well and that on the Kjeragbolten. You see, that’s exactly what I mean,” I continue our conversation. “An untrained young woman has her photo taken in such a dangerous location just to get a few likes. That’s not normal. Just a few years ago, people took blurred, out-of-focus photos of themselves. It didn’t matter whether the shots were overexposed or underexposed and today many people want to produce the absolute super shot and it doesn’t seem to matter whether you strip naked as a woman in front of all these people and then present yourself to the whole world. It’s just crazy, really crazy.”

“Can you send me the photo?” says the Indian woman, who was naked on the rock a moment ago and reveals herself to be Norwegian. “Gladly,” replies Tanja, who had taken her photo. “I wanted to show the men,” she explains as we exchange phone numbers. “What do you mean?” Tanja wants to know. “So many men have been photographed naked on the Kjeragbolten that I, as a woman, wanted to take a stand against them. What the men can do, we women can do too.”

A glance at the clock reveals 4:30 pm. We set off to avoid getting into the dark. We take the small detour that Henrik, the parking lot manager, recommended. “Unbelievable,” I say reverently as we lie close to the cliff edge and look down on the Lysefjord a thousand meters below us. The view is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful and spectacular of our entire travel life. A ship or ferry makes its way through the fjord at this moment, dragging gentle waves behind it that spread out like a V, only to crash against the cliffs and die minutes after they have formed. We lie there for minutes, gazing into the intoxicating depths. Ajaci seems to be aware of the unusual moment, because he is lying between us, also looking down and not making a sound. “This is where the base jumpers jump down,” I say. “Crazy,” replies Tanja. “Yes, that’s it. It is said that 53,000 jumps have already been made from up here. There have been 136 accidents so far and 12 jumpers have given their lives for the thrill. When I was 22 years old, my then boyfriend Wolfgang and I also wanted to come here to jump down. For some reason, we never did it,” I say, thinking back to those days. “It’s a good thing you never put it into practice,” whispers Tanja. ‘Yes, fine,’ I say.

On the way down we meet the Englishman again. “Is that expedition vehicle down there in the parking lot yours?” he asks, walking in front of me. “Yes.” “I bought an old fire engine in Germany and am in the process of converting it into an expedition vehicle,” he explains. “Well, then I wish you lots of energy and stamina,” I say. “Yes, I probably need that,” he replies and starts to ask me about our bimobil. Engrossed in conversation, we stray from the path, which is not good in these mountains. “Where is the path actually?” asks Tanja. We stop and look around. “We have to go right,” I say confidently, and we walk in the direction indicated. Suddenly, crevasses and glacier tongues block our way. “We have to turn back,” says the Englishman, which is why we climb back up the mountain a little. Unexpectedly, a crevasse opens up in front of us. “Can your dog jump over it?” asks the man. “Hm, definitely, but he could also slip and fall in there,” I say. “Well, I’ll see you later. I have to catch up with my friends,” he says, jumps over the crevice and runs off. Tanja and I look at each other in surprise. “Now he’s been asking you about building cars all this time and then he just disappears,” she wonders. “Never mind, we’ll find our way back without him,” I reply, feeling a slight nervousness rising within me. I study the rock massif in front of me with concentration. “Don’t make any mistakes now”, goes through my head. I move forward, reading the rock and the course of the crevasses, only to find myself standing in front of an even bigger rockfall a few hundred meters further on. “We have to get up there,” I decide, pointing upwards. Then we try another attempt. “Maybe we should go back to where we started?” Tanja ponders. “I hope not,” I say, glancing at my watch. The sun is slipping lower and lower, taking its bright daylight with it bit by bit. “If we don’t get out of here before dark, this hike will be life-threatening, ” an alarming thought shoots through my brain. I try to keep my nervousness under control and walk back a little to look for another passage. To our left we descend for an estimated 800 meters, to our right more and more snowfields and deep crevices appear. “Can this be true?” I reproach myself for not paying more attention to the road because of a trivial conversation and thus getting us into this awkward situation. “What a load of shit!” I curse under my breath. Below us I discover another tongue of snow. I bypass them in the direction of the abyss because there is a possibility. The only problem is that behind every supposed possibility lurks a barrier that was previously invisible. I hurry ahead, climb into a crevasse, leave a snowfield to the left and discover a promising passage that leads us upwards. “That looks good!” I shout. At the top, I see a hiker in the distance. 10 minutes later we are back on the track. Without wasting much time, we continue our descent. In the meantime, we seem to be the last. Tanja runs ahead with Ajaci. They move like two gazelles while I lower myself backwards on the iron chains to take the strain off my knees.

7 hours after our ascent, we reach the parking lot safe, sound and happy. Henrik is still there. “Can we take the ferry from the valley to Stavanger?” I ask, because that would be the easiest and most beautiful way out of the mountains. “Unfortunately not. For a week now, there have only been ferries for cars. You’ll have to drive your truck through the mountains on the outside.” “Okay, thanks for the great information and conversation. We wish you a good life,” I say goodbye. “I wish you the same. Above all, many more fantastic adventures and good health.” “Thank you Henrik,” Tanja calls out. Then we drive back up the narrow, single-lane pass road. Serpentine for serpentine. The sun has already set over the exceptionally beautiful mountain landscape. I carefully steer the Terra up and down. On some hairpin bends at walking speed. Leaving the mountains behind us, we find a spot for the night on the shore of a lake at 21:00. I turn the ignition key. The engine stalls. Tired, exhausted and filled with this eventful, exciting and inspiring day, we crawl into bed and fall into a deep, restful sleep…