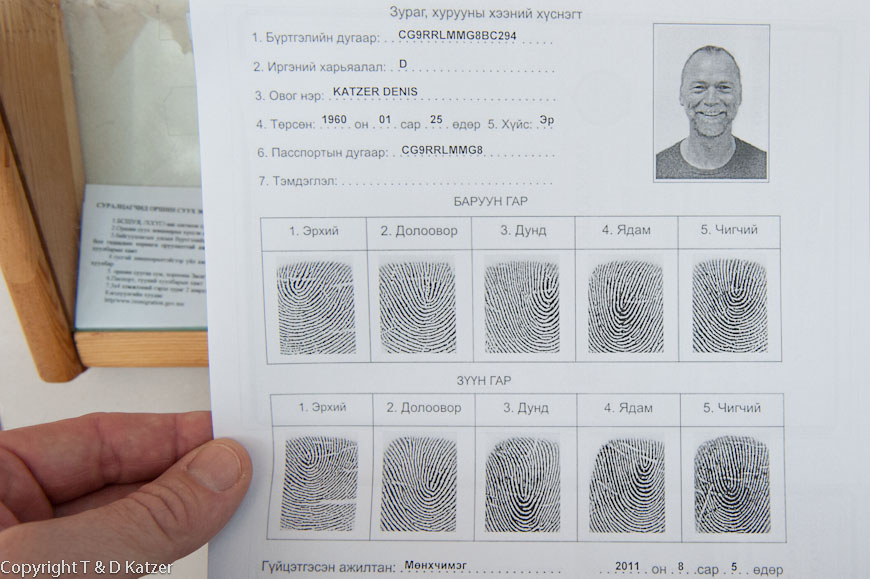

Hooray we have our visa

N 49°01'802'' E 104°01'571''

Day: 16-17

Sunrise:

05:38 h/05:48 h

Sunset:

8:17 pm/20:30 pm

As the crow flies:

247

Daily kilometers:

400

Soil condition:

Asphalt

Temperature – Day (maximum):

26 °C

Temperature – day (minimum):

20 °C

Temperature – Night:

17 °C

Latitude:

49°01’802”

Longitude:

104°01’571”

Maximum height:

1315 m above sea level

Time of departure:

9:00 a.m.

Arrival time:

5:30 pm

Average speed:

60

Tanja got our work visa for 365 days yesterday without any problems. Hurrayaaaa!!!! With the help of Saraa we made it. The miracle I spoke about at the beginning of the year has now manifested itself. We are now owners of a Mongolian I-D card. Once again, this situation shows me how the firm belief in the supposedly impossible, the unfeasible and what many call utopian can become real if you really want it to. If you put everything you’ve got into it and go about it with confidence, perseverance and positive thoughts. There is no such thing as impossible. That is a fact. Everything works, with minor restrictions, almost everything. Mother Earth or “All That Is” or as other people say, God, taught me in the deserts of Australia to firmly believe in my desires and not to tense up or harden along the way. “Let it flow Denis”, I heard over and over again for three years. Later, after I had lamented this statement with Mother Earth for a long time, it was modified slightly. It was then called “Active flow Denis”. Which means: “Do everything in your power to realize your wishes and dreams. But if there is a high, insurmountable concrete wall on your path, don’t go through it with your head and break your skull, but go around this wall and continue to pursue your goal”. This means going your own way calmly, accepting unplanned events and keeping the set goal in mind despite detours. However, we have our visa without which our expedition would not be possible.

Move our base camp to Erdenet

Today at 8:30 a.m. there’s a knock on the door. It is Ganbold. As the owner of the apartment is Ganbold’s niece and she is currently abroad, Ganbold manages the handover of the apartment. “You can round up to €300,” he says when Tanja wants to give him the agreed rent of €280. Because we don’t want Ganbold, who has helped us a lot, to be dissatisfied in the end, we round up the amount and give him another 20,000 (12,- €) Tugrik for his efforts. He agrees and laughs. In the meantime, it’s knocking again. Ulzii, Tagi and the minibus driver Tsag are now also on time. All together we carry 350 kg of equipment from the fifth floor to the yard. Before setting off, Tsag first changes one of his ailing tires. Then he expertly shuffles all our luggage into the minibus. We say goodbye to Ganbold. “Have a safe journey,” he wishes us and disappears into the traffic in his jeep. A little later, our vehicle also rattles through U.B. in a north-westerly direction. After just 50 km, one of the rear tires loses air. We find a workshop in a village, at least that’s what the shabby little hut is called, and fill the tire. Then we drive through a fantastically beautiful Mongolian hilly landscape in bright sunshine. “Somehow this area looks familiar to me,” I say to Tanja and ask Tsag if this road leads to Darhan. “Yes, that’s where we have to go. But just before Darhan, we turn left towards Erdenet,” he replies. “I thought so,” I say, thinking with every mountain we cross how hard it was when we were struggling over the endless hills on our bikes 1 ½ years ago. “Look Denis! Over there is the little house where we found accommodation on the way to U.B.,” Tanja suddenly calls out. “That’s right. I remember well how the landlady cooked us a delicious soup and we could warm ourselves up there,” I reply and think back fondly to that time. Whenever we see a hill that has demanded a lot of our strength or the last sunny resting place where we had lunch, we exclaim joyfully and tell ourselves the story we experienced there.

“Tell me Denis, what do you actually believe in?” Tsag suddenly asks me. “Oh, that’s a short question with a long answer.” “No problem, we’ve got the whole journey,” he says and laughs. So I tell him about my experiences and conversations with Mother Earth that I had during our 7,000 km march through the outback. I talk about my experiences in Hindu temples, my opinion about Buddhism, the Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox churches. “And you’re Mormon?” I want to know. “Yes, I am,” he says and explains to me that he spent two years in Siberia as a missionary. “Our religious community was founded by Joseph Smith in 1830. Today we have around 8 million members worldwide. Half of us live in the USA. There are also many Mormons in Great Britain and Scandinavia. I was one of about 45,000 missionaries proclaiming our faith worldwide and I am proud of it. Our community is growing rapidly. And if I’m honest, I have to say that our faith is the only true faith there is. But I also accept all other faiths. You know, a lot has been falsified in the Bible. Some of it has nothing to do with reality. They are fairy tales. Our faith is based on the truth,” he says and wants to know if I consider Joseph Smith, like the Mormons, to be a true prophet. “I can’t allow myself to judge that. I only know your faith through your stories. I would need to know more to be able to form an opinion. But it is quite possible that he was a prophet. Who can judge the opposite? It’s a matter of faith and if you believe it, it’s the truth for you,’ I reply and try to change the subject as Tsag’s knowledge of English is not sufficient for a profound philosophical discussion. I look out of the window and watch the green hills whizzing by. It smells of thousands of herbs and flowers. “Nature still seems to be in order here”, I think to myself, and because I have worked so incredibly hard over the last few months, weeks and even days, I feel a leaden tiredness pressing down on my eyelids. Only in passing do I hear Tsag trying to make his faith palatable to me. Suddenly the minibus slows down. “Are we there yet?” I ask, coming out of a short sleep. “We’re out of gas,” says Tsag, shrugging his shoulders. “We’re out of gas? What do we do now?” “There’s a petrol station up ahead,” Tsag says calmly and lets the minibus roll down the hill. We just make it to the gas pump. How lucky that there’s a village here and a petrol station to boot,” laughs Tanja. “We refuel the old minibus and then we stutter along. The diesel tank was empty down to the last drop. Now all the pipes have to fill up again until the old thing recovers from this vacuum.

At 17:30 we reach the town of Erdenet with a population of around 70,000. It is one of the typical Mongolian towns. Blue, red, brown and gray corrugated iron roofs of the small wooden huts shine into the blue sky. In between are many yurts in which shepherds live right in the city. We drive through the not exactly appealing center, characterized by communist box high-rises that belong more to the ugly category. Then it’s up a hill. Tsag brings his minibus to a halt in front of an old wooden hut. A wooden fence surrounds the approx. 800 square meter garden in which wild grass grows. At the lower edge there is a crooked little house in which the outhouse is located. Welcome to the gateway to the wilderness. Naraa, Saraa’s sister, comes out of the hut and greets us warmly. The vehicle is quickly unloaded and everything is carried into the hut. We get the living room all to ourselves. Our equipment fills the entire anteroom. We lay the sleeping mats on the carpet and roll out our sleeping bags on top. The days of beds and comfy mattresses are obviously over for the coming year. And of course there is no running water. The water is fetched with a small handcart about 500 meters from the house at a public water point. 30 liters cost about 200 Tugrik (23 euro cents). Each of the inhabitants has to buy their precious water at these water points. There is electricity in the log cabin, but the wiring, especially the plugs and cables, look life-threatening. Although we knew that we would turn our backs on civilization, or what we call civilization, this moment is surprising. It is precisely in moments like these that we realize again and again what luxury we have come from. The gateway to the wilderness often sounds more romantic in stories than it feels in reality. It will take us a few days to settle in here.

Bilgee visits us that very evening. Bilgee was recommended to us by the local Mormon chief. He is said to be a reliable man and would like to accompany the expedition. Because of the horse-drawn wagon and the immense challenges that await us during this expedition, we need at least two experienced men. At least one of them should be familiar with horses and the construction of a horse-drawn carriage. Taagii our translator, whom I have always mistakenly called Tagi, arranged this contact. It is already dark when Bilgee and two other Mongolians enter the hut. A lively, long conversation immediately ensues, of which we of course understand nothing. Taagii, whose English has improved a lot in the last few days, makes a great effort to translate. “What do you mean?” I ask Tanja. “Looks very daring. I wouldn’t want to have any problems with this man on the road. What’s your opinion?” “I have no idea. It’s really hard to say,” I reply. We discuss the details, the distribution of tasks and the salary. He agrees. “I’m a hunter and can provide us with meat on the way. Is that all right with you?” he wants to know. “Although we know that there is still plague in Mongolia, especially among marmots, we say yes. (Plague is a serious infectious disease in humans and rodents caused by the rod-shaped gram-negative bacterium Yersinia pestis. Today, plague occurs almost exclusively in Africa, Asia and South America; it has virtually disappeared from Europe and North America).

During our last Mongolia expedition in 1996, we learned that it makes no sense to prohibit the Mongols from hunting. It is precisely such bans that have led to interpersonal problems. Back then, our companions simply left the expedition for a few days and went hunting, especially for marmots. Sometimes they weren’t there exactly when we needed them. We want to avoid this from the outset.

“What’s your impression Taagii?” I ask to get another opinion. “I don’t know. He talks too much. Before we decide whether to take him or not, I’d talk to Ulzii’s uncle first.” “Good suggestion,” I reply, whereupon we tell the man to decide tomorrow evening. He nods, says goodbye and leaves the log cabin.

A little later, Ulzii’s uncle Tsaagaan arrives. The man, who is about 1.70 meters tall, has a friendly and appealing face. It makes a good impression on us from the very first moment. In the course of the conversation, we hear that he is already 56 years old. Because of the often harsh lifestyle, this is already considered old in Mongolia. “Is he still fit?” I ask Taagii. “I’m fit,” Taagii translates the words of the man who, like Bilgee, agrees to all the conditions. Also with receiving his first salary after a week and the rest only after the expedition. “If you need anything on the expedition, you will of course receive money from us. However, we have had bad experiences when we pay the entire salary in advance or weekly. Sometimes our companions have simply run away during an expedition. So this is nothing against you personally but has something to do with our experiences,” I explain. “No problem,” he smiles. “I’ll be happy to accompany you.” “Can you also build a horse-drawn cart?” I ask. “Sure, I drove a horse-drawn cart myself for two years,” he replies. “What about alcohol? Do you drink a lot?” I ask, as we haven’t had very good experiences in this area either. “Drinking? No. Only rarely,” he replies with a serious expression.

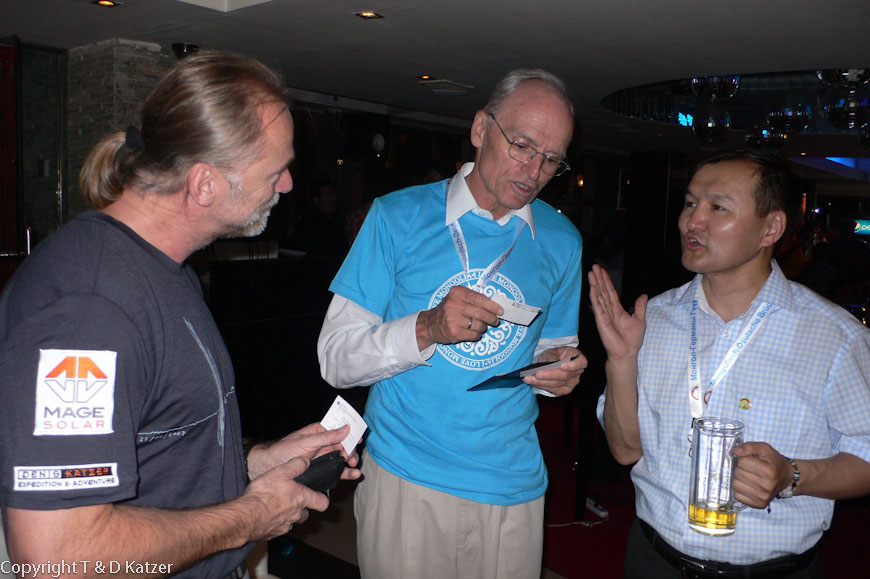

After he has also said goodbye, we all talk about the two men together. “Well, Ulzii would be very happy if you chose his uncle. He would much rather be traveling with him,” Taagii translates. Ulzii, who is to be our translator when Taagii leaves us again, understands very little English. Nevertheless, he can guess the meaning of the words and nods. “Saraa, who has arranged our visa so far, organized and arranged Ulzii, Tsaagaan and much more for us, would also prefer us to choose her relative Tsaagaan. Even if our feelings waver back and forth between the two men and we are very reluctant to say no to either of them, the decision is already obvious. We don’t want to go against Ulzii’s feelings and we don’t want to disregard Saraa’s recommendation under any circumstances. “I think we’ve decided on Tsaagaan,” I say to Taagii and Ulzii after a brief consultation with Tanja. Both are relieved and Ulzii’s face brightens up.

To our readers!

Because of the unspeakable number of events and challenges, I hardly get to write at the moment. For example, I am already sending this update from a very exotic location. Human disappointments, ups and downs, bad weather, dishonest horse sellers and much, much more make the beginning of this expedition an adventure that we would not have expected in this form. Unfortunately, we also face major challenges time and again with our sensitive technology. Live reporting, even if it takes place a few days late due to the recording of the experiences, is a challenge that is hard to describe, sometimes almost impossible and beyond my strength. Exhaustion, tiredness and constant tension make every successful update of the homepage a gift for me. Tanja and I are happy that no storms have swept away our laptops or thieves have enriched themselves in the night. So please stay tuned.

We look forward to your comments!