The way over the ice and arrival at the White Lake

N 51°21'785'' E 099°21'046''

Day: 101

Sunrise:

08:14

Sunset:

17:58

As the crow flies:

15,55

Daily kilometers:

40

Total kilometers:

1146

Soil condition:

Ice, snow

Temperature – Day (maximum):

minus 18°C

Temperature – day (minimum):

minus 25°C

Temperature – Night:

minus 35°

Latitude:

51°21’785”

Longitude:

099°21’046”

Maximum height:

1800 m above sea level

Time of departure:

12:30

Arrival time:

17:00

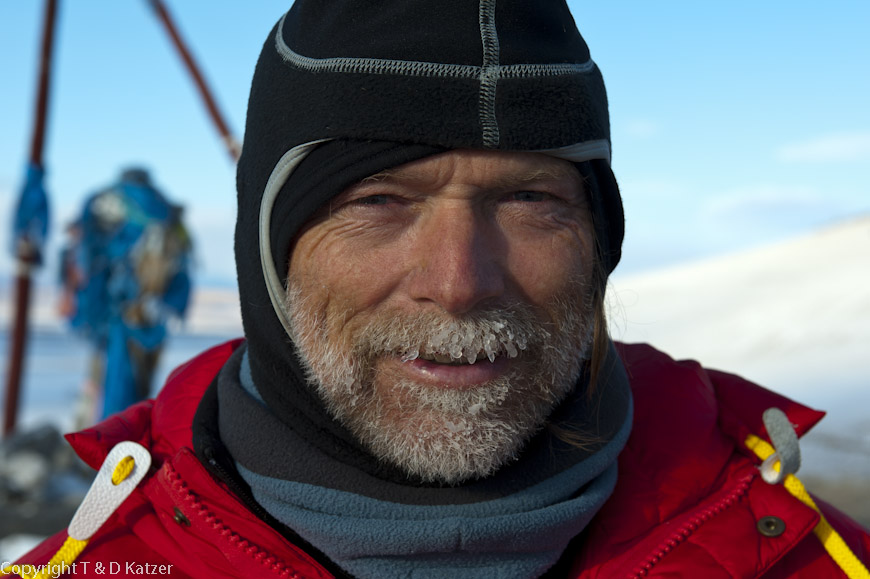

In the rising sun, the thermometer remains at minus 25 °C. Shivering, we slip out of our sleeping bags after this extremely cold night. The zippers, inner tent walls, clothing, cameras, batteries, simply everything is frozen stiff and covered in frost. Even though it was minus 35°C tonight, we haven’t pulled out all the stops yet. We still have fat down jackets that are rated down to minus 35 °C and have already been tested by us. We also have several pairs of woolen underpants and undershirts as well as overpants in reserve. If, as expected, we don’t arrive in Tsagaan Nuur today and the thermometer drops to minus 40 °C, the spare clothing is reassuring. They are the last trump card to parry the cold.

We crawl on all fours into the frozen morning. Everything around us seems to be crystallized. The horses shiver and their coats are covered in white ice. The lake’s ice cover sings and cracks incessantly under the enormous tension. Our feet feel like icicles. As nothing is moving in Bilgee’s tent, we are startled for a moment. He won’t have frozen to death, will he? “Bilgee! Bilgee! Wake up!” shouts Tanja. “Tijmee,” it replies. “Are you all right?” asks Tanja anxiously. “All right,” he replies and comes out of the tent a little later wrapped up in his Winterdeel.

As soon as the first gentle flames of our campfire flicker into the steel-blue sky, we slip out of our shoes and put our feet over it. It takes a while until they are warm. Then we put our shoes back on. As soon as the feet have developed a little warmth of their own, they are also able to warm up the shoe. Without fire, blood circulation could only be stimulated by a long endurance run. Tanja’s feet, on the other hand, remain numb even after the warm-up. She now runs around our camp, jumping up and down to stimulate her blood circulation.

After a hot, freeze-dried meal, we pack up the camp as if in slow motion. In these extreme temperatures, the only chance of survival is activism. Giving up, sitting down and moaning, staying put and waiting for better times or anything to do with phlegmatism would quickly lead to certain death. Bilgee is a fantastic example of how to survive a winter out here. He is always busy and always on the move. Bilgee proved to be a very hard-working and helpful person throughout the trip. Without a doubt, we couldn’t have had a better partner. “Daraa bajartaj majhan” (“Goodbye tent”) is how he bids farewell to his frozen dwelling today. Again we laugh at his humor and again I say goodbye to our fabric house with confidence. I fold up the tent sheets that have hardened from the frost. We haven’t had a chance to let them defrost in the sun for many days now before packing.

Around midday we are sitting in our saddles and are just about to set off when Bilgee disappears without a word of explanation. “What’s that supposed to mean?” asks Tanja, freezing. “I wish I knew,” I reply and zipper up my down jacket, which I’m trying out today. Their advantage over the Deel is their light weight. As a result, I don’t find it difficult to get on the horse and I am much more agile.

Ten minutes later, Bilgee arrives on horseback, accompanied by the Mongolian with whom he spent so much time talking last night. “Oglooniimend” (“Good morning”) is how we greet him. “Ogloonimend,” he replies kindly and takes Sharga and Bor from Tanja’s hands to lead her. “He will show us a safe way through the sea labyrinth,” explains Bilgee with a smile. “But the ice cover isn’t safe. It might not support us,” Tanja replies to me. “I don’t know,” I reply indecisively. “Don’t you think we should take the detour and go via Renchinlkhumbe? Then we could follow the track and not have to ride over the frozen lakes. It would be pretty stupid to break in and die just to save two or three hours.” “It would be safer, but Bligee really wants to take the shortcut,” I reply. “And what do you want? What do you feel?” “My feeling is neutral today. I think the passage across the lake is fine because of the cold night last night. What do you think? What does your gut tell you?” I ask Tanja. “It actually feels better today than yesterday. We’ll do what you decide to do,” she replies confidentially.

“Okay,” I say to Bilgee. “Let’s give it a try.” “Bilgee smiles and rides ahead with the shepherd. A few minutes later we meet the Mongolian who was drunk yesterday and tried to help us across the ice. Thank goodness he is sober today. “My name is Batsog from the Tuwa tribe,” he says cheerfully and joins our group. “A tuwa? Tuwas are also called Tsataans, aren’t they?” asks Tanja. “Yes,” I reply, pressing the heel of my healthy leg into Sar’s flank.

It doesn’t take long and we reach the spot where we wanted to cross the lake yesterday. The men don’t hesitate for long and step onto the ice. At intervals of about 100 meters, Batsog, the shepherd and Bilgee each lead a horse across the ice. “Tttzzuuuunng! Tttzzuuuunng! Tttzzuuuunng!” it cracks as if an eerie thunder is racing under the ice surface to blow it to pieces. But nothing happens. The men reach the opposite bank safely. Tanja now follows with an initially queasy feeling. Since I film and photograph, I bring up the rear. It only takes 20 minutes to get all the horses safe and sound on the opposite side of the land. The men quickly get into their saddles and trot hurriedly over the hilly countryside until we reach the large river that made it impossible for us to continue yesterday. At a bend in the river which is completely covered in ice we want to attempt the crossing. “Wait!” I shout to Tanja as the men all ride across the ice together. “Tttzzuuuuuuuunng!” the horses’ hooves suddenly crack so loudly that they shy away and the men freeze in their movements like pillars of salt. When nothing breaks, our companions ride on carefully. Then Tanja and I follow.

“From here on, there are no more lakes or rivers that could be dangerous for you. From here it’s only about 15 kilometers to Tsagaan Nuur,” explains the helpful shepherd, shakes our hands and rides back to his home.

Batsog, on the other hand, is staying with us. He also has to go to Tsgaan Nuur and leads Sharga and Bor. At a fast trot, you head up a hill on the other side of the lake labyrinth. While I lead Mogi, Tanja drives Sharga and Bor with great fervor and joy. Bilgee and Bartsog laugh at their enthusiasm. At the highest point of the mountain crouches an Ovol, as always, to whom we pay our respects and ride around three times with good wishes. The view of the lake district below us is fantastic and the feeling that a winner feels just before reaching the finish line is slowly growing in us. “We’re going to make it today,” says Tanja, beaming with joy. “I’m sure of it,” I reply with a smile.

On the other side of the mountain, we trot into another high valley. We ride through a fairytale forest that is covered in ice crystals. The horses emit white clouds of breath into the minus 18 °C cold day. But now, so close to the finish line, our adrenaline levels are so high that we no longer freeze. When trotting fast, Sar often slips with one of his legs. My heart stops in horror every time. Then we reach electricity pylons that form a winding line and show us the way to one of the most remote villages on our Mother Earth. To Tsagaan Nuur.

At the foot of another mountain, Bartsog hands Tanja the lead rope from Sharga and Bor. “I live over there,” he says, pointing to a small hamlet and gallops off. Now we climb the top of the mountain at a more leisurely pace. At the top we are greeted by another Ovol. It is the Ovol of Tsagaan Nuur. Below us, the snow-covered village lies peacefully in a wide valley. We get off the horses, tie them to a wooden shelter and look towards our destination. “So there it is,” I say and feel gentle waves of deep satisfaction rise up inside me. “Yes, there it is. Looks nice,” says Tanja. “Our home for a while,” I reply. “Until we go to the Tsataans in any case,” Tanja agrees.

Then we sit down on the wooden bench under the shelter and drink hot tea and eat the obligatory Russian cookies, which I actually like under the circumstances. Suddenly a small motorcycle rattles up the hill. A policeman and a military officer are sitting on it. I look towards them, somewhat surprised, and when they stop next to us I feel a slight nervousness. Has word gotten around that we are here? Impossible. Perhaps a coincidence? The two men get off their iron companions and come to us. They return our friendly greeting. “Passports,” says the policeman, asking to see the papers. “Oh, they’re stowed in the duffel bags on the horses,” Tanja replies with a friendly laugh. The man lets it go at that. We offer them hot tea and cookies, which they gladly take. They are amazed to hear where we come from and that we want to spend the winter here. “Well then, you can show me your passports later when I get back to my police station,” says the policeman. “We’re happy to do that,” I reply. Before the men leave, we take a farewell group photo. Then they rattle down the mountain we rode up on their motorcycles and disappear into the distance.

“Shall we?” I ask Tanja and Bilgee. “Yes, let’s ride down,” they reply. As we ride into the lovely-looking, sprawling log cabin village of Tsagaan Nuur, we are followed by the curious glances of some of the residents. I feel like an explorer from a past century. We stop at a small log cabin with a sign on the gable telling us that we can buy food here. Bilgee calls Ayush, Saraa’s cousin, to inform him of our arrival. It doesn’t take long before a young Mongolian woman comes to the log cabin and waves to us in an euphoric, friendly manner. “Please come with me. It’s not far,” she asks us to follow her. Just 200 meters further on, we come across a wooden shelter covered with countless cow pats. Some cows stand in its shelter and eat hay. The woman, who introduced herself to us as Tsendmaa, opens an old gate cobbled together from sheet metal and wood. We lead our horses into a yard of around 1,000 square meters, which is completely surrounded by a typical wooden shed. Our convoy comes to a halt next to the large log cabin, in front of an old Russian truck. An old, sprightly man, who must be Ayush, immediately helps his adopted daughter Tsendmaa unload the horses.

We let Mogi run around freely as there are no sheep on the estate. But Jack, the family dog, sees Mogi as an intruder. It only takes a few minutes for the two of them to get into each other’s fur. I can only separate them with difficulty. No one takes any particular notice of the incident and everyone continues to unload the horses. Once our luggage is on the snow, I happily turn to Bilgee, squeeze his hand and give him a hug. “We have actually made it to Tsagaan Nuur. “Tschin setgeleesee bajrlalaa”, (“Thank you very much”) I say and hug him for the first time. Bilgee is also visibly moved and hugs me, laughing. Then Tanja comes and hugs him with all her heart. “We’re a great team,” I say overjoyed.

“Come inside,” Tsendmaa invites us to leave the cold of the evening. We are happy to enter the log cabin. A wall of heat almost knocks us over. We are no longer used to this kind of warmth because we have been living outside for the last few weeks. “Sit down,” says Tseden-ish, Ayush’s 89-year-old wife. We get hot milk tea and Boortsog. Overjoyed and content, we sit by the roaring cannon stove, drink hot tea and try to talk to each other with our hands and feet. My eyes glide through the doll’s house. It’s just like you can imagine a log cabin in Siberia or northern Mongolia. The cupboards are painted with colorful ornaments. There is a kind of ancestral table on one wall on which certificates and many pictures of the entire family hang. A television flickers in front of a colorful tapestry. A small sofa with red and white cushions and a floral blanket is the bed of Tscharaa, who at 12 years old is the youngest adopted daughter of Ayush and Tseden-ish. The 85-year-old Auyush and Tseden-ish sleep in two separate beds on opposite sides of the 50 square meter room. The only cooking area is the potbelly stove behind which the colorfully painted, wooden dish rack and waist-high cupboards of the same color nestle against the wall.

Pale light shimmers through the partly broken window panes, on which the cold has painted ice flowers and licks at us. “Hooray, she can’t touch us at the moment,” I murmur quietly. “What did you say?” asks Tanja. “Oh, the cold. It can’t harm us in here anymore. We’re sitting in the nest. We’ve made it,” I say happily. “Yes, we made it,” says Tanja with a happy expression on her face.

“Come on, I’ll show you your yurt,” says Tsendmaa. We follow her behind the log cabin and stand in front of a beautiful little yurt. “Our home for the next seven months,” says Tanja and steps inside through the small wooden door. Inside, our little cannon stove, which we bought in Mörön and had already used in Saraa’s yurt, is roaring. Shagai, Saraa’s friend, has already installed a new wooden floor and rolled out the linoleum and carpeting. “Thank you very much for heating things up,” says Tanja to Ayush and Tsendmaa. “Is our equipment here yet?” I ask. “Yes, apart from a few small items, everything has already arrived. We have stored it in our ambaar (storage shed) for the time being,” says Tsendmaa, who unfortunately doesn’t speak a word of English. But this is hardly a problem as we understand everything we need to understand in connection with Bilgee and the language we have developed with him.

After visiting our Mongolian house, Ayush assigns Mogi a place behind the yurt. There we lay a horse blanket on the cold ground and chain him to a wooden fence. Then we are invited to dinner in the log cabin. There is a hearty rice soup with meat, potatoes and onions. Tsendmaa wanted to cook extra for Tanja because she is a vegetarian. However, as it is certainly not possible to survive as a vegetarian in Mongolia, Tanja decided weeks ago to eat meat from time to time. “When we get back home, I’ll stop eating meat again,” she says. I’m glad that she is so relaxed and makes it easier for herself to survive when traveling.

It is already late when we go to our yurt, roll out the sleeping mats on the freshly laid wooden floor and crawl into our sleeping bags. It doesn’t get cold in the yurt until 1:00 am. I get up, light the fire in the stove again and enjoy the luxury of having a warming fire in the tent.

We look forward to your comments!