On stormy seas to the sperm whales

N 69°19'28.8" E 16°07'05.7"

Date:

02.10.2020

Day: 061

Country:

Norway

Location:

Andenes

Daily kilometers:

0 km

Total kilometers:

5444 km

Soil condition:

Asphalt

Sunrise:

07:11

Sunset:

18:31

Temperature day max:

14°

Night temperature min:

9°

Departure:

10:30

Arrival time:

18:00

(Photos of the diary entry can be found at the end of the text).

Click here for the podcasts!

Link to the current itinerary

(For more posts click on one of the flags in the map)

06:30 am. Soft light creeps through the windows of the Terra and settles on our comforter. Caressed awake by the peaceful light, I gaze out at the mirror-smooth North Sea and watch as the first rays of sunlight illuminate the seemingly endless strip of horizon in a yellow-orange band. “You’re awake already?” asks Tanja, lolling. “Take a look outside. We’re in for a fantastic day,” I reply, yawning softly. “Oh how beautiful. Not a cloud in the sky and the sea is as smooth as a child’s bottom,” she replies with a smile. “What time does the hotel reception open?” I ask. “From 9:30 a.m., I think.” “We should be there in good time to buy tickets.” “After breakfast, I’ll go ahead and ask,” Tanja replies, dangling her feet off our cozy bed. “Wooouuuuuiii!” Ajaci howls happily from his cave under our bed. “Wooouuuuuuiii!” he howls again as Tanja scratches his ears with her feet. “We’re going to play ball first,” she says, whereupon Ajaci, like every morning, can hardly contain himself with unbridled joy. While the two of them play “catch the ball” on one of the freshly cut lawns in front of one of the houses by the harbor, I do my morning exercise. Afterwards, we eat breakfast, looking out of the window and watching the seagulls as they swoop close to our terra and then settle in small groups on the smooth surface of the water. “Ajaci and I saw a large, gray-white seagull this morning during our aurora mission that kept hopping in front of us,” I begin to recount our experiences from last night.” “Was the aurora as beautiful as it was on our first aurora nights in Lofoten?” “It was completely different. It was simply amazing, the way they passed right over the houses at the harbor. You should have been there,” I enthuse, “I was so tired. Did I miss much?” Tanja is a little annoyed that she didn’t go. “We will definitely be able to admire a few more Northern Lights nights on our trip to the North Cape and to be honest, I don’t know if it was smart to pull an all-nighter before the whale safari. Unlike you, I’m now dog-tired and don’t know how I’m going to get through today.” “Ha, ha, ha. The tiredness will vanish into thin air when you see the first sperm whale.” “I hope so,” I reply, yawning like a lion.

“We’ve got the tickets!” Tanja shouts enthusiastically, rushing into Terra. “Great, so the ship wasn’t fully booked?” “No, according to the woman at reception, it’s only half full. There’s a school class and a few tourists on board with us.” “And when does it leave?” “We’re supposed to meet at the reception next to the restaurant at 10.30 a.m. for a museum tour. Then they’re going out on the old M / S Reine.” “M / S Reine?” “It’s a seal hunting ship that they started building before the Second World War.” “Poor seals,” I reply. “The woman told me that the construction of the ship was delayed until 1949 because of the war and it was never used for seal hunting.” “Oh good, so no seal blood on board,” I say.

“And you are the journalists who have been accredited for a tour with us?” a man of about fifty speaks to me in English. “Yes. And you’re the captain?” I answer questioningly. “Ha, ha. No, I’m one of the guides,” he replies with a laugh. “Is that great expedition vehicle out on the quay yours?” he wants to know. “Yes. It really is a fantastic mobile. Great fun,” I reply in a friendly manner. “I believe that. Surely you’ve been on the road for a while?” “Almost 30 years. But not just with the motorhome. That only came into our lives almost two years ago,” I explain. During our brief conversation, it turns out that Stefan is Swiss and that he and his wife Nathalie emigrated to Norway just a few months ago and bought a house here in Andenes. “Maybe we can have a little chat later,” says Stefan, because in the meantime some guests have gathered around us, waiting for instructions and information. “I’d love to,” I reply, looking forward to the tour.

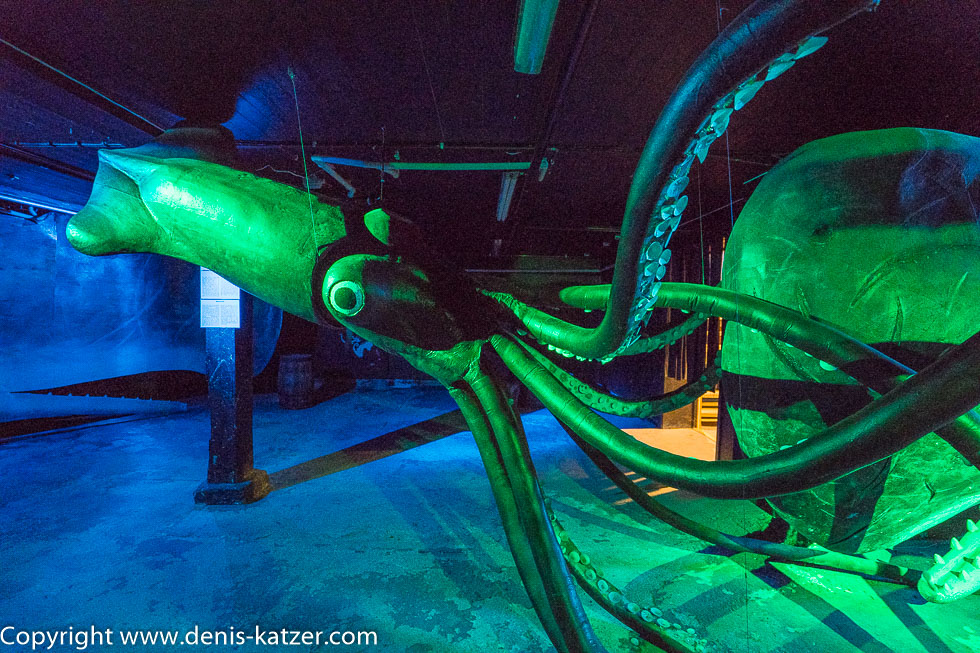

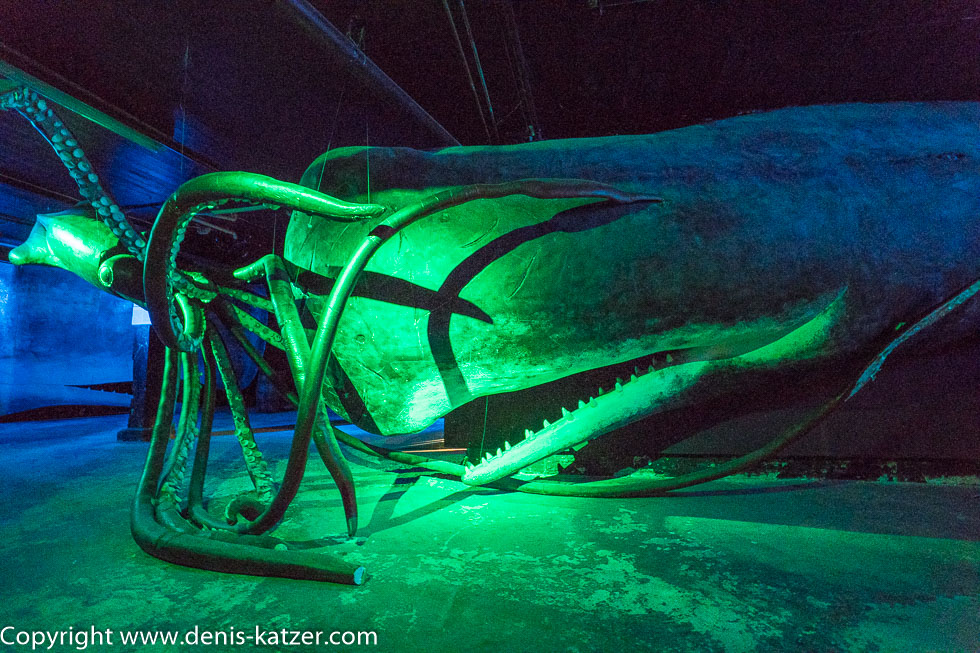

We descend the steps to the basement of the building where the whale museum is located. “The sperm whale is the largest of the toothed whales, whose males are more colossal and heavier than the females. They are found in all oceans,” Stefan begins his explanation, standing in front of a sea chart. “Its German name refers to its head, which can be up to a third of its total length and sticks out like a pot, or pott in Low German. Its English name is Sperm Whale because the melon, an organ in the whale’s head, contains a waxy substance that looks like sperm. This substance is called spermaceti, which was used to produce candles, high-pressure lubricants, hydraulic fluids, inks, cleaning agents, cosmetics, plasticizers and tanning agents, and was one of the reasons why this wonderful creature was almost wiped out. Whale oil was used to make soaps, ointments, soups, paints, gelatine and cooking fats, as well as margarine and shoe and leather care products. Whale oil was originally even needed to produce nitroglycerine. Which was urgently needed by the army until after the First World War. The hunt for sperm whales reached its peak in 1964, when 29,255 specimens were killed to make the aforementioned products.

The current population of sperm whales is estimated at only 360,000 animals, of which around 5,000 live in Norway. Today, the animals are threatened by the increasing pollution of the oceans, among other things. The stomach of a young sperm whale was found to contain 100 kilograms of garbage, including the remains of fishing nets, ropes, bags, packaging tape and plastic cups.

The males are known for the long distances they travel and venture into polar regions and marginal seas that lie on the edge of the oceans and are only separated from the open ocean by island chains, ridges or deep-sea trenches. The aggregations of females and juveniles, on the other hand, live in the tropics and subtropics.” “They like it just as warm as I do!” one of the guests interjects. “Hi hi,” his companion is the only one to laugh at the shallow joke. “Here at the northern end of the island of Andøya in Vesterålen, the seabed drops off to a depth of 1,000 meters just off the coast,” Stefan continues his explanation. “These are fantastic conditions for the sperm whale, which feeds on cod, tuna, monkfish, smaller sharks and even larger crustaceans, and dives at this depth for octopus, which it likes to hunt. Giant squid specimens up to 10 meters in size have been found in the stomachs of dead animals and scars from the suction cups of giant squid have been found on the skin of sperm whales. This suggests fierce battles between whales and squid. However, it must be said that nothing like this has ever been filmed and the exact circumstances of such fights are completely unexplored. Incidentally, the sperm whale is one of the deepest diving marine mammals on our planet. The males, which consume around one and a half tons of food per day, dive longer and deeper on average than the females, and the discovery of fish in their stomachs, which live exclusively at depths of over 3,000 meters, confirms that the sperm whale can even reach such extreme depths.” We listen spellbound to his comprehensive explanations for just under an hour. At the end, the likeable Swiss asks us to follow him into a hall where one of the few sperm whale skeletons in the world is located. We stand in amazement in front of the 15.8 meter long skeleton of a whale that stranded on Andanes beach in 1996. We learn that large bulls of 20 meters in length weigh over 50 tons and their brains weigh up to 10 kg, making them the heaviest in the entire animal kingdom. “Based on tooth trophies over 30 centimetres long from the time when sperm whales were still hunted on a large scale, we conclude that there were specimens that were much longer and weighed over 100 tons,” we hear. Curious, I walk around the skeleton and take a few photos until I realize I’m the last one in the hall. I quickly hurry outside into the sun-drenched day to the former ship designed as a seal catcher.

The heavy diesel engine is already bubbling and the guests are boarding.

While the old ship with its wooden hull sails out, Stefan and his colleague give us a safety briefing. We are also told that, with a bit of luck, we have the chance to get baleen whales in front of the cameras as well as sperm whales. “So keep your eyes peeled for finback whales, pilot whales and dolphins. We’ll recognize what’s swimming in the water in front of us by the blow and let you know. Good luck and have fun!” “Great,” I say and climb onto the upper deck with Tanja and enjoy the harbor exit. “Over there is the island of Senja,” I say, pointing to the land mass about 40 kilometers northeast of us. “Our next destination,” says Tanja happily.

Although there is no wind over the sea, the waves are getting higher and higher, forcing us to hold on tight. The M / S Reine begins to sway considerably, rises above the rolling wave crests only to rush into the next wave trough a fraction of a second later. Suddenly Stefan is standing next to us. We pick up our conversation where we left off two hours ago. I only realize far too late that I’m feeling a little queasy in my stomach. “Sorry Stefan, I need to concentrate a bit on the waves. I think I’ll go forward to the bow of the ship,” I say, and we sway our way to the front of the ship. The wind blows a cool breeze towards us. The aged but technically state-of-the-art wooden barge plows through the choppy North European sea. No sooner has the boat tackled another wave crest than it falls back into the deep valley. There at the bow we have the feeling of standing on a ski jump. If we didn’t hold on to the cold steel railing, we would be hurled into the sea in a high arc. I’m getting increasingly nauseous. I’m less and less interested in whales now. Sea spray sprays up and blows over us, and some of those on board are also struggling with nausea. After almost three hours at sea, there is still no sign of whales. “What have I let myself in for here?” I think to myself. The organizer promises to encounter whales normally after 40 to 60 minutes. But what is the normal case? Despite the blue sky, the North Sea is stormy. “Where do the damn waves come from?”I am struck by a new thought. Wuuummms, the bow of the 30 meter long and 6.8 meter wide M / S Reine crashes into one of the million wave valleys as if there were no tomorrow. The first guests use bags to shake off their nausea. “Let’s go down to the middle of the ship,” Tanja suggests, because Stefan had already mentioned during his safety briefing where the quietest place on the ship is. As if drunk, we stagger into the middle of the ship. We have to cling to the stairs down so that we don’t just bang on the steel planks below us. “Oh, I’m getting sicker and sicker,” I say meekly. Then we sit down on one of the benches. Although I’m dressed warmly, I start to feel cold. “That’s because seasick people hardly move at all,” I find out later from Stefan. But movement is out of the question at this moment. I just sit there stock-still, my gaze fixed on the distant horizon. Just doing everything I can to somehow achieve stability. Then suddenly something stirs. Gunnar, the 94-year-old former captain of the M / S Reine, climbs into the lookout to keep an eye out for the blow of a sperm whale. “Did you see that?” Tanja asks gently. The captain’s father climbs into the lookout at the age of 94 and in this heavy swell.” “I didn’t see it,” I say with an effort, as I don’t want to put my head down under any circumstances. “Already in the 16. and In the 17th century, Dutch whalers used the region to hunt for whales. You’ve been at sea for weeks and I feel sick after just three hours”I think. Although I have often been exposed to rough seas in recent decades, I have never felt this sick, at least I don’t remember it. With the help of the underwater microphones on the boat, the crew is able to hear the sperm whales, as the whales use a form of echolocation to find their prey and to orientate themselves. They emit clicking sounds that can be clearly heard with the hydrophones. Apparently, they are also capable of generating sound pressure waves of over 230 dB, which, according to one theory, may also be capable of stunning their prey. No wonder, when you consider that the take-off of a jet plane is 120 dB, the launch of a rocket 140 dB and the shot of a cannon at 150 dB make your ears ring. Despite my nausea, I look up and see a crew member standing on the bridge, scanning the surface of the water for a bubble with his binoculars, just like old Gunnar in his crow’s nest. Stefan explained to us that the blow is the air exhaled by whales after diving, saturated with moisture and expelled at high pressure. Due to the lower outside temperature, it condenses and becomes visible as a fountain of mist. “You can tell which animal is exhaling its breath by the different blowing of the whales,” he explained to us this morning. “A bearded whale, for example,” he continued his fantastic explanation, “has two blowholes and usually produces a V-shaped fountain of mist. The right whale has a blowhole that can shoot up to 8 meters into the air. Blue and fin whales, on the other hand, have a pear-shaped blow. The blue whale has the highest blow at 12 meters. With a body length of up to 33 meters and a body mass of up to 200 tons, it is the heaviest known animal in the history of the earth. Toothed whales, on the other hand, only have one blowhole. In the sperm whale it is on the left side and its blowhole is at an angle of approx. 45° to the top left. This allows us to see exactly which animal has surfaced.”

So it was the blow that gave the whales away before the days of underwater microphones. When the whalers spotted a blow, they rowed or sailed there and killed the beautiful animal with harpoons. “Whale to port!” shouts old Gunnar after more than three hours and 32 kilometers on the high seas, whereupon those who can still jump to the left side of the ship, pull out their cameras and look out over the water. I pull myself together, grab the system camera with the 400 mm lens and shuffle over to the left-hand side of the boat. “Are you OK?” asks Tanja sympathetically. “I’m fine,” I fib. You can actually see a bubble. The excitement is great, the cameras are clicking. I wonder how some of the guests want to capture the distant blow-out with their cell phones. The captain steers his boat towards the whale, and as soon as we get closer, he throttles back the engines and positions the M / S Reine at right angles to the animal lying in the water like a tree trunk. The former seal catcher is now swaying considerably in the high waves, making you want to spit the deep green stomach contents over the railing to feed the whale. I try to keep the camera as steady as possible in all the swaying and press the shutter release. I have no idea whether I’m immortalizing the water or the sky. “Dive!” it calls over the ship’s loudspeakers, so we know that the sea creature will show its fluke at any moment and dive into the dark depths for another hunt. “Ohhh! Ahhh!”, the guests shout in delight as the whale stretches its tail fin into the blue sky just moments after the diving call and its heavy body disappears for around 30 minutes. I drag myself back to the wooden bench in the middle of the boat and am relieved that a whale has appeared. “Now we can finally drive back,” I say to Tanja, wringing a relieved grin from my face. “We’ve located another whale!” I’m startled to hear minutes later by a joyfully excited voice rattling through the on-board loudspeakers. “Shall I bring you a blanket?” asks Tanja, because I’m now shivering from the cold and because I’ve been tramping through wet grass during the morning’s Aurora activity and my feet are still in damp shoes. “Yes,” I answer meekly. A young Norwegian is lying on the bench next to me, his face positively green. Every few minutes he rises with a groan to spit the rest of his stomach contents into the bag with a terrible retch. Then, completely exhausted, he sits back down on the bench and trembles just like me. A girl puts a blanket over him and says a few reassuring words. “Poor guy,” I think, because I’m doing much better compared to him. 20 minutes later I hear the call “Whale!” This time, everyone who is still fit rushes to the starboard side of the ship. “Should I take a photo?” asks Tanja. “I’ll manage,” I reply curtly, take the camera and sway to the right side of the railing in time with the waves. Through the viewfinder I can see the bubble rising into the sky. If I didn’t mind, I would be absolutely fascinated to be able to observe such a huge animal with my own eyes. The M / S Reine reaches the sperm whale before it dives back into its dark realm of the deep sea for at least 30 minutes. Shivering from cold and weakness, nausea and a choppy sea are not good conditions for taking acceptable photos. I pull myself together, concentrate and press the shutter release…