Perpetrators create victims, victims become perpetrators

N 11°35'03.4'' E 104°55'52.1''

Date:

03.06.2017

Day: 704

Country:

Cambodia

Location:

Phnom Penh

Latitude N:

11°34’03.4”

Longitude E:

104°55’52.1”

Total kilometers:

23,937 km

Maximum height:

10 m

Total altitude meters:

71.177 m

Sunrise:

05:35 h

Sunset:

6:21 pm

Temperature day max:

35°C

(Photos of the diary entry can be found at the end of the text).

Dust billows over the endlessly polluted streets of the capital. Everything seems bleak, broken, desolate in this view. Under the terrible memories of the Killing Fields I have just visited, I feel as if an all-encompassing darkness has darkened my heart, my psyche and my thoughts. An all-encompassing hopelessness is just about to spread inside me. Although the big city is dominated by the typical hustle and bustle of Asia, my thoughts fly back to April 17, 1975, when the Khmer Rouge conquered the then 2 million metropolis and deported the entire population to the countryside within a few days under false promises. What remained was an abandoned, deserted ghost town, inhabited only by around 20,000 people, mainly party functionaries and other elites. One of the reasons for this was the political goal of founding an ideological, Maoist-inspired, self-sufficient peasant state in which cities were considered counter-revolutionary and were therefore to be dissolved nationwide. Some of the mercilessly displaced persons died of exhaustion on the march, later from the consequences of forced labor, hunger, disease and targeted killings. Under the rule of the criminal Khmer Rouge, life for the civilian population turned into an absolute and indescribable hell in which two to three million Cambodians, i.e. a third of the entire population, died.

“Here it is,” the old rickshaw driver pulls me out of my thoughts and stops his vehicle. Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, is written in a dull blue on a grayed sign. Even from the outside, the former school, which was misused as a torture center by the Khmer Rouge between 1975 and 1979, looks terrifying and repulsive. It is with mixed feelings that we enter the S21, the Genocide Museum, in whose archives thousands of confessions, life stories and photos have been discovered that provide a comprehensive insight into the Khmer Rouge’s killing machinery of the time. In 2009, the museum was added to the Unesco World Heritage List. Also the pictures of the surviving prisoner Vann Nath, which he had to paint on behalf of the camp director Kaing Guek Eav, known under the pseudonym Duch.

“Over there you can take an audio guide”, says a young girl smiling at us. We put on our headphones and follow the instructions of the voice, which first asks us to take a seat on one of the stone benches in the shade to hear one of the most incredible stories of how misguided people tortured their own people to death in order to expose alleged traitors. While our gaze falls on the rusty barbed wire that still surrounds the facility today to prevent the prisoners from escaping or from throwing themselves to their deaths out of sheer desperation from one of the floors, we follow the factual reports. We learn that the former classrooms were converted into prison cells and torture chambers in which between 14,000 and 20,000 people from all parts of the country were imprisoned from 1975 to 1979 and tortured in ways that can hardly be described in words, with meticulous care being taken to ensure that none of those tortured died before confessing. If this happened anyway, it could happen that the torturer himself ended up on the rack. Under torture, people admitted everything, as long as the torture stopped. As confessors, they were then deported to one of the approximately 300 Killing Fields, where they were mentally and physically mutilated and found redemption by being beaten to death or having their throats slit.

We have now entered one of the buildings. In some of the converted classrooms, pictures of completely mutilated people hang on the wall, showing how the tortured had been tied to iron bedsteads in order to torture them. The images were photographed by the prison liberators as proof of the atrocities. Because the employees of the torture center fled from the Vietnamese army invading the city, 14 inmates were still alive. A week later, there were only seven survivors out of 14,000 prisoners. The other seven succumbed to their injuries, weakness and illness. I force myself not to close my eyes to the horrifying cruelty and look at the bodies deformed into a pulp of flesh and blood. I am overcome with nausea and feel like running away. I am aware that in this case I would run away from a picture, a blurred photograph that mercilessly shows the incomprehensible horror. Basically, you shouldn’t show something like that to a visitor, it answers from the depths of my brain. Only if we humans show ourselves again and again what humanity is capable of will it possibly have the chance to prevent such excesses of violence from the outset in the course of its evolution. But is this line of thought correct? Has humanity changed significantly since the Stone Age, when people were beating each other with clubs? Don’t all the current wars, in some of which even poison gas is used against innocent civilians, prove that human beings, regardless of race and skin color, have lost none of their inherent perfidious cruelty? Don’t the wars and conflicts currently raging just prove that the way we slaughter each other has changed?

Tanja and I walk on in silence. Shaken by horror, as if an earthquake had just split the ground beneath our feet, we reach the next former classrooms. Rooms where girls and boys sat to be taught languages, math and perhaps even history before the Khmer Rouge seized power. What an irony, because at that time they would certainly never have thought of themselves becoming victims of the cruelest atrocities in human history, just because they later pursued a middle-class profession, owned books, wore glasses, lived in a city or were simply the children of people who had learned a foreign language.

The rules for prisoners in S21 were regulated. Talking, laughing, crying, any kind of communication was strictly forbidden. Anyone who did not follow these instructions was punished with electric shocks or beatings with the cane. Shouting was also strictly forbidden. The interrogation techniques were also precisely defined. The torturers had to follow them just as much as the tortured. For example, one of the questions was: “You must answer my question accordingly. Do not turn them away. Or: You have to answer my questions immediately without wasting time thinking. Or: If you are being whipped or given electric shocks, you must not scream under any circumstances…

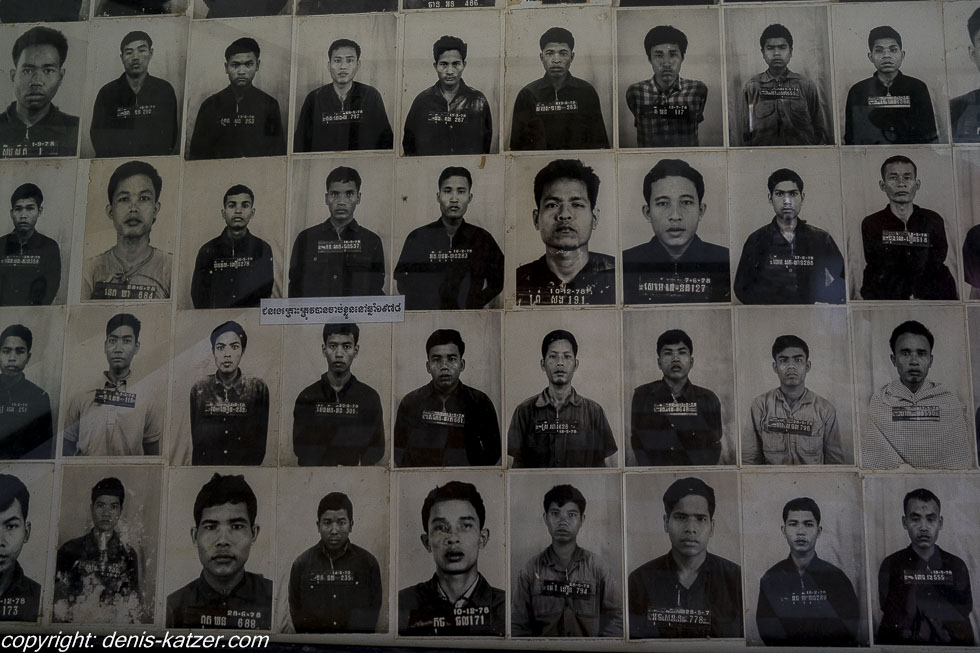

We stand in front of hundreds of photographs showing the faces of young people. In many of the pictures we see visibly frightened victims. Not far from this picture wall is another, on which the faces of the young torturers gaze out at us. I stand in front of it and study it carefully. Is there a difference between the torturer and the tortured? How does a person become a torturer? What drives him to abuse his own kind with electric shocks, to crush their limbs with thumbscrews, to tear out their fingernails, to hang them from gallows until they fall unconscious, to squirt acid into their noses? inserting insects and creepy-crawlies into every orifice of women and men or submerging them in vats of water to simulate death by drowning (waterboarding was also one of the many inhumane interrogation methods used by the CIA after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 against prisoners. (Waterboarding was also one of the many inhumane interrogation methods used by the CIA after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 against prisoners in secret prisons in order to extract a confession at any cost).

“No difference,” I whisper to Tanja, who is standing next to me. “Like no difference?” she also asks quietly, as if talking like she did back then would result in the most severe punishments. “The faces of the torturers look exactly like the faces of the tortured. I can’t see the evil in their eyes.” “That’s right. The faces of the torturers look exactly like those of their victims.” “Yes, the henchmen are also victims of the sick regime of a surely mentally ill Pol Pot. Certainly, the approximately 1,720 employees of the torture center, who were responsible for abusing between 14,000 and 20,000 people in just four years, were not all mentally ill. It is surprising to me, however, that humans are actually more willing to kill many of their own kind in order to save their own lives. If this were not the case, such institutions would not function. Basically, the survival instinct of the individual contributes to killing others. Right or wrong does not seem to play a role, even if the Khmer Rouge were obviously historical monster criminals, many played along to save their own skin. History seems to repeat itself again and again. Mao Tse Tung, Josef Stalin, Adolf Hitler, Genghis Khan, Idi Amin, Pol Pot, Ivan the Terrible, Joseph Mobutu, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and Kim il-Sung are some of those who top the list of the greatest mass murderers,” I say thoughtfully.

Suddenly we are standing in front of the photos of two foreigners. The young Australian sailors David Lloyd Scott and Ronald Dean, who docked on the wrong coast at the wrong time during their sailing trip. They were also imprisoned here as alleged spies, interrogated, horribly tortured and finally beaten to death in the Killing Fields. I stand horrified in front of the pictures and read their unfortunate story, listening to the audio guide about the incomprehensible misfortune of the young men who, along with other foreigners, fell into the hands of the torture regime and met an abrupt end as complete innocents.

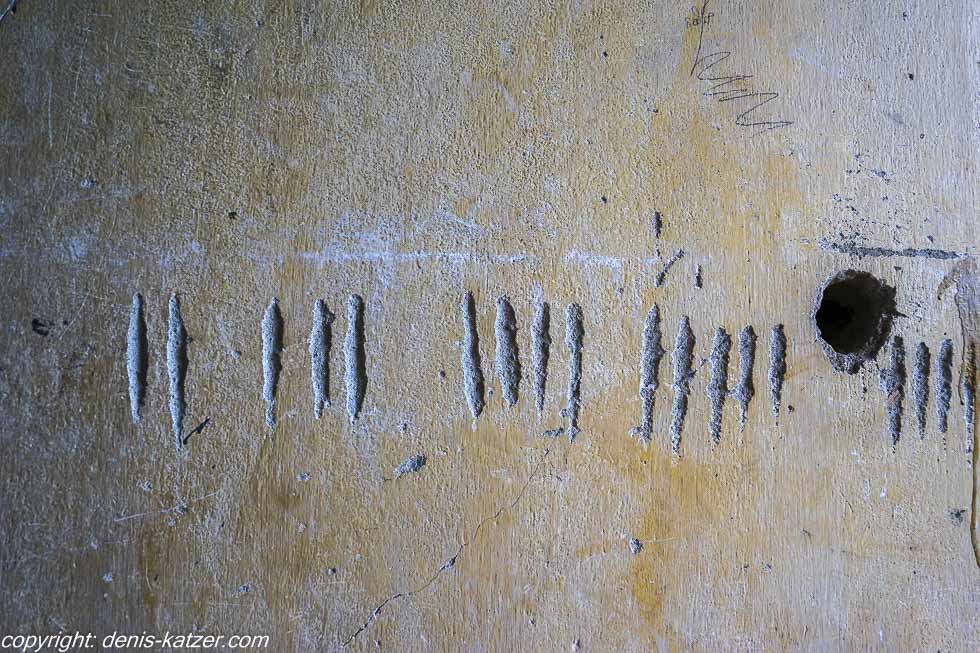

After three hours we looked at most of the mass and individual cells. We saw dried bloodstains of the tortured on the concrete floor, scratched lines in the stone wall made by torturers who had never attended school and thus assigned the keys to the individual cells. We saw torture instruments of every conceivable kind, looked at incredible pictures by the surviving painter Vann Nath, which radiate so much suffering that it is almost unbearable. During this time, the audio guide told us stories of torturers and their victims. On the way to the exit we hear: “Kaing Guek Eav, commander of S-21, stated during an interrogation: “I and everyone else who worked in this place knew that everyone who came there had to be psychologically destroyed and eliminated by constant labor and not allowed to get out. No answer could prevent death. No one who came to us had a chance to save themselves.”

I experience the way to our accommodation as if in a trance. The pictures and stories of the S21 prison and the Killing Field are unforgettably burned into my brain. My mind cannot grasp the scope and cruelty of what has happened. It is too big, too evil, too unbelievable to be grasped with logic. I simply cannot understand how something like this could happen at the end of the 20th century on our beautiful Mother Earth. The rule of the Khmer Rouge plunged their country into one of the worst and most insane experiments in human history. An experiment on living humans to create a new human race using brute force, which was to be geared exclusively towards basic needs. The great China supported this spawn of disease, the Western world looked on or negated the acts of violence.

I feel dead inside, I feel anger and rage coming up. Incredible anger towards the people who caused all this, who were responsible for torturing and beating to death almost three million fellow citizens in a bloodlust. These are people who have not yet been prosecuted for this. Who were never punished for their terrible crimes. Pol Pot himself only died in 1998. He also got away with it. A few leaders are housed in modern luxury bungalows near Phnom Penh airport, only to be tried by an international tribunal 38 years after their crimes. Until then, they lived at large. By the time the sentences are carried out, most of them have died of old age. Even the torturers of the prisons and executioners of the more than 300 Killing Fields were for the most part allowed to lead a normal life after the end of the Khmer Rouge regime.

The current government has certainly not helped to put those responsible behind bars in time. Of course, the current prime minister of Cambodia is considered extremely corrupt, allegedly does not shy away from murder and was one of Pol Pot’s generals. What can you say? I just can’t think of anything else. The world is not necessarily fair, would be a standard answer, but that doesn’t help me either. Stunned by the most horrible museum visit of our lives, we sit in one of the street restaurants. I nibble listlessly on my beer. Completely atypical for me, but there’s nothing else that gives me pleasure at the moment. “I think I’ve had a shock,” I say after a long while, which we spend in silence. “I’m not feeling well either,” I hear Tanja say as if in a trance.

The image of Cambodia has changed since visiting the Killing Fields and S21. Suddenly I no longer see the smiles on people’s faces. I remember that everyone here is a victim or was a perpetrator. At least the older generation. Do we want to continue traveling in a country like this? Does it make any sense at all? Will we still find joy, openness and lightness here? Will our minds recover from the traumatic experiences of the realistically made documentary? an inner voice asks me. But what good will it do the people of Cambodia today if I suddenly suffer from depression? What do they gain from it? Or what do I get out of it? Or Tanja? It’s all nonsense. Or? Life goes on. Don’t take past events too personally. It’s not your fault. You can’t change history. The atrocities of the Khmer Rouge are over. – Although parts of this organization are said to still linger underground. My thoughts are bubbling, getting confused, branching out, trying to find a meaningful way out. “I have to write about it,” I break our renewed silence. “You really want to do this to yourself?” asks Tanja. “No, I definitely don’t want to. But I think I have to write about it. Firstly, I can then process what I’ve experienced better and secondly, I believe that you have to report on such crimes. Even if it only helps a little to ensure that something like this never happens again.” “I’m sure many people have already written about it,” Tanja tries to prevent me from having to read all about this monster crime again while I’m writing. “I’m sure thousands have already written about it. The net is full of it. But I personally didn’t know much about the Khmer Rouge and Pol Pot. I had never dealt with it because it was on the other side of the world. But now we’ve cycled all the way here, visited the Killing Fields and the torture center. Somehow these experiences are now part of our personal history. A reason to write about it. A reason to pass on this knowledge.” “Hm, a good explanation. I was actually just trying to protect you. I personally wouldn’t do that to myself, but I understand if you want to get back into it.”…

If you would like to find out more about our adventures, you can find our books under this link.

The live coverage is supported by the companies Gesat GmbH: www.gesat.com and roda computer GmbH http://roda-computer.com/ The satellite telephone Explorer 300 from Gesat and the rugged notebook Pegasus RP9 from Roda are the pillars of the transmission.